If you’ve ventured on to Crypto Twitter this year, you may have seen a tweet from the meme account WTF Happened in 1971?

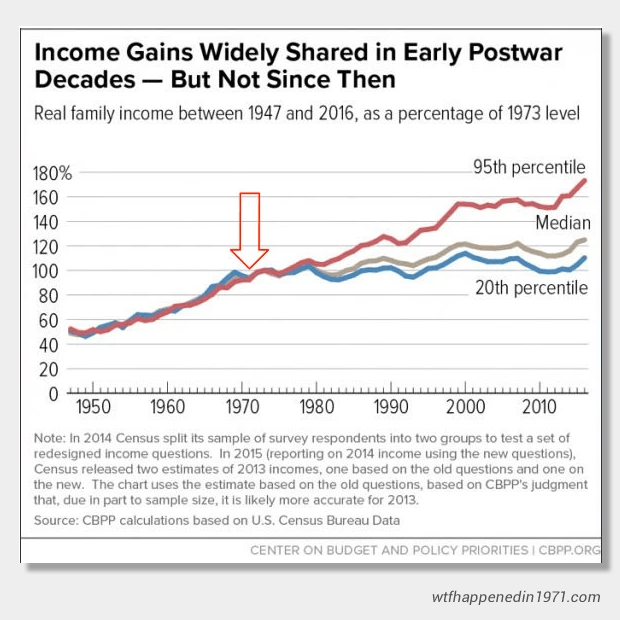

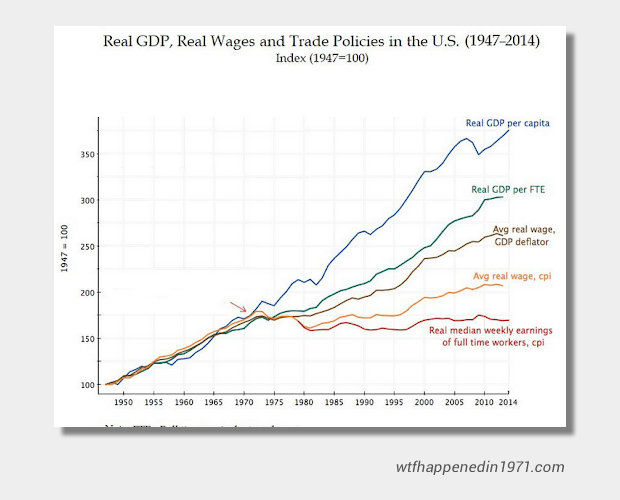

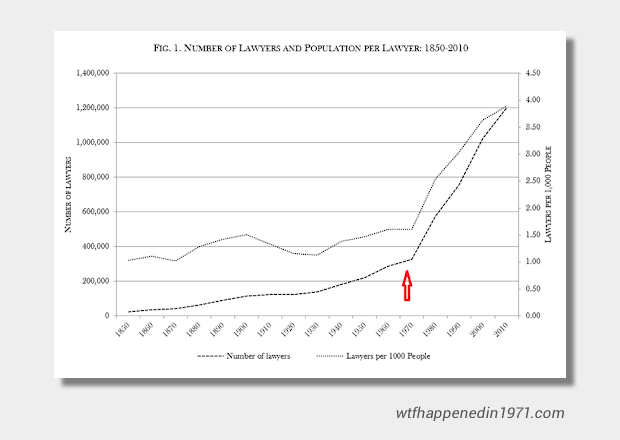

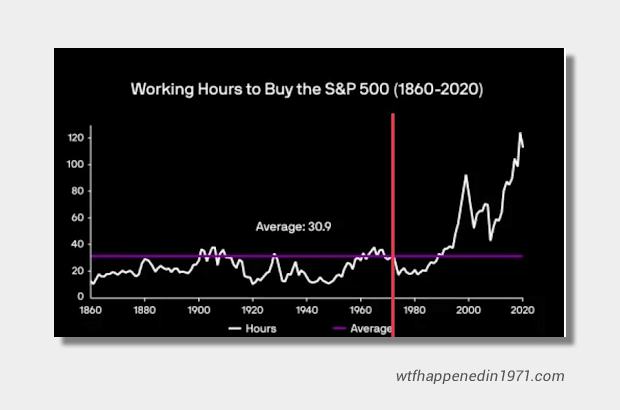

Created in March, the account posts numerous times a week to its fast growing fanbase of 10,500 followers. A typical post features a graph that shows how inequality has grown in recent years, inflation has skyrocketed and how ordinary people are being priced out of houses and stocks due to low wage growth. Somewhere on the chart there will be a little arrow pointing at 1971, which highlights when the rot set in.

And it invariably poses a question like: “WTF happened to wages in 1971?” Or, on a chart showing ever-widening political polarization: “WTF happened in 1971 that led to such a divergence in political thought?”

Its followers notice similar phenomena and contribute to the meme by tagging them in. This week someone reposted a New York Post article showing a decline in the happiness of lower socio-economic status white adults since the early 1970s, asking: “Gee I wonder #wtfhappenedin1971???’

So what did happen in 1971?

The WTF Happened in 1971 website suggests that all of these disparate effects are connected to President Richard Nixon calling time on the Bretton Woods financial system which tied the value of the world’s reserve currency — the U.S. dollar — to gold.

The ‘gold standard’ as it is known, underpinned global finance from 1944, when the World War II Allied Nations, including the U.S., Canada, Western European nations, Australia and Japan, negotiated the rules of the international monetary system with fixed exchange rates between currencies. This took place at a hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. At the time the U.S. controlled two thirds of the world’s gold and insisted the system was based on gold and the US dollar.

The system meant that in theory you could redeem $35 USD for one ounce of gold – although in actual fact it was illegal for US citizens to hold gold between 1933 and 1974 after the government ran into trouble backing the currency during the Great Depression. Foreign governments could trade dollars for gold at that rate however. The government again ran into trouble backing the currency with gold in the late 1960s, after printing too much money to pay for things like the Vietnam war and various welfare programs, which was the rationale for Nixon killing the system on August 15, 1971.

Yeah, but it was a good thing

The effects of this are contested to say the least. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) for example suggests that fears at the time that the move away from gold would bring the era of rapid growth to an end were misplaced. “In fact, the transition to floating exchange rates was relatively smooth, and it was certainly timely: flexible exchange rates made it easier for economies to adjust to more expensive oil, when the price suddenly started going up in October 1973. Floating rates have facilitated adjustments to external shocks ever since.”

For many traditional Keynesian economists leaving the gold standard behind has provided governments with the flexibility to use activist monetary and fiscal policies to respond to, or prevent, economic crises. For example, without the Federal Reserves ‘unlimited’ quantitative easing program (money printing) this year, the economy may have fallen into such a deep hole the U.S. may never have clambered out of it. And Greece’s inability to inflate itself out of its sovereign debt crisis in the years after the global financial crisis was part of the reason it had to embrace crippling austerity measures. Surveys of mainstream economists suggest that 9 out of 10 think returning to the gold standard would be a disaster.

No, leaving the gold standard was a disaster

But WTF 1971 tells a different story. It showcases various graphs highlighting that from 1971 onwards productivity increased while wages flatlined; GDP surged but the share going to workers plummeted; and house prices went through the roof leading to Americans’ ‘savings’ becoming inextricably tied to home values. It suggests that around the world episodes of hyperinflation increased, currencies crashed more frequently and there was a spike in the number of banking crises. The personal savings rate fell off a cliff, the incarceration rate went up by a factor of five, divorce rates shot up and the number of people in their late 20’s living with their parents increased exponentially.

Most horrifyingly of all, the number of lawyers quadrupled.

The site and Twitter account was founded by former 3D graphics designer Ben Prentice and Bitcoin podcaster Heavily Armed Clown — also known as Collin from The Bitcoin Echo Chamber. Both live on the east coast of the U.S., and met when Prentice pitched himself as a guest on Collin’s podcast.

Prentice discovered Bitcoin in 2017 and fell deep into the Austrian economics rabbit hole. That’s a strand of heterodox economics beloved by goldbugs that suggests Keynesian economists have got it all wrong, fiat is worthless paper and gold is the answer. Although hugely influential among Bitcoiners, Austrian economics is shunned by mainstream economists and frequently criticized for lacking scientific rigor and not relying enough on mathematical models and macroeconomic analysis.

“Austrian economics is really just trying to dispel the logical fallacies inherent in Keynesian logic, starting at first principles and then building you way up from there,” says Prentice. However the pair have one major difference to the Austrians in that they believe Bitcoin is the answer that gold never was, he continues:

Our belief is that gold itself failed as a money. And that’s hard for the Austrians to get because they’ve been advocating for gold for so long. But the reason gold failed as money is because we had to come up with paper in the first place to scale it and we know how many problems come with paper.

Collin says he was trading penny stocks, alternating between pump and dumps and a value investing strategy “which isn’t really a real thing” when he stumbled across Presidential candidate Ron Paul’s End the Fed while researching the underlying causes of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. This led to the work of famed Austrian economists Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard — who coined the term anarcho capitalism.

“That’s where we found commonality,” says Collin. “And it was between our economic discussions talking about history, talking about money, talking about human action, that we came upon a lot of inflection points in the data, which happened around 1971.”

The first few graphs for the site were taken from the Wikipedia entry on Bretton Woods, and they kept seeing more and more charts that suggested the same thing.

“We started collecting those and other ones,” says Prentice. “We started arguing with economists on Twitter and eventually, I think it was Collin’s idea, he was like: ‘Well, we’ll just throw these up on a website and just ask WTF Happened?’ and the rest is history.”

So far in 2020, the site has had around 400,000 visitors, and is growing its audience month on month.

Collin says they’ve considered their arguments carefully.

“We spend the vast majority of every day especially Ben and I just in private, discussing these things back and forth and sending, you know, trying to poke holes in our ideas.”

Rising inequality the result

The most obvious effect of moving away from the gold standard, was the ability for governments to print as much money as their hearts desired. As Collin puts it:

The temptation to print money is the greatest temptation in the whole world.

To illustrate how this harms individuals, Prentice uses the analogy of a pie as representing the economy, with the slices representing the money in circulation. “As we’re printing more money, all we’re doing is taking existing slices and making them smaller and smaller and smaller,” he explains. “Each unit is now worth less. Nothing new has been created. You still have the same pie, but now your slice of the pie is much smaller than it was before.”

Collin says that this results in people trying to store their wealth in other ways, which has resulted in runaway asset price inflation since 1971.

“When money is debased, and it loses its value over time, people store their wealth in assets,” he says. “That’s why it’s common financial wisdom, to diversify your assets, to invest in stocks to invest in bonds to invest in gold, buy a house. The more assets you own, the better off you’ll be in the long run, because all of those assets are going to increase in price because of inflation.”

The net effect is a massive increase in economic inequality because the wealthier you are, the larger the percentage of wealth you can afford to hold in illiquid, volatile assets. Working Joes however — the median household net worth in America is $97,300 —need to devote most of their dollars to rent and food and insurance, and have a larger share of capital in depreciating assets like cars.

“This system is very, very much tilted towards the wealthy,” says Prentice. “A very wealthy person would hold 80 to 90% of their wealth in business interests and equities, right, and those inflate. This is the money of the wealthy, but the access to those assets is almost nil for the poorest.”

This would be less of a problem if wages had kept up with inflation. While average hourly wages in the US have roughly increased in line with CPI, that’s just one way to measure inflation. One of the most telling charts on the site shows that the number of working hours to buy a single unit of the S&P 500 has increased to an all time high of 126 hours today, up from an average of 30.9 hours since 1860.

Depending on how deep down the rabbit hole you want to go, there are ramifications everywhere.

Collin explains there’s an economic calculation that can be performed normally whereby as capital is accumulated in bank savings accounts, interest rates come down. “Then people are more likely to borrow money and go out and try and engage in new productive ventures,” he says. “Creating new money and artificially suppressing the central bank interest rate is distorting that economic calculation.”

He says our crazy financial system is the reason hugely profitable companies like Apple still borrow billions of dollars to buy back their own stock.

“Why would they borrow money which they then have to use to pay interest in order to buy back their own stuff? The answer is the replacement cost of assets is higher than the replacement cost of capital.”

Like the famous chapter of Freakonomics that linked the Roe vs Wade Supreme Court decision on access to abortion in the 1970’s to the decrease in crime two decades later, they’re also not discounting some less intuitive ramifications.

“We believe that a lot of second, third, fourth and fifth order effects happen as ripple effects that happen outwards of monetary policy,” explains Collin.

When we look at things like obesity, right, and you say that is not related to the end of the gold standard. Are you sure? Because people have to eat a whole lot more subsidized food than they did 60 years ago and in America, the number one subsidized crops are sugar and corn.

They now believe the system has become so distorted, it’s no longer genuine capitalism. Collin points to the 52% of young adults who are now forced to live at home with their parents instead of building their own wealth, buying a house and starting their own families. “You can’t afford to do any of those things and you just look at the system that exists and you say: this is broken, right? You’ve always believed in capitalism, but now you’re seeing this system that they’ve called capitalism is broken. But Ben and I posit that this is not capitalism, this is something completely different. This is social monetarism.”

Although there are some pretty obvious drivers of the 100 days of protests and riots in America following the death of George Floyd, rising inequality has played a big role, says Prentice.

“I absolutely think so. I think that people get out in the streets when things aren’t going well. People are frustrated, because they don’t feel like this system is working at all, and that they work their whole lives at crappy jobs.”

But maybe they’re wrong

Collin and Prentice sound pretty convincing, but economics is a frustratingly complex area and even the world’s best economists are frequently way off. In December 2007 the Wall Street Journal asked 51 economists to predict what would happen in 2008. Not a single economist predicted a recession, much less the dramatic events of the Global Financial Crisis, even though the subprime mortgage crisis had begun five months earlier.

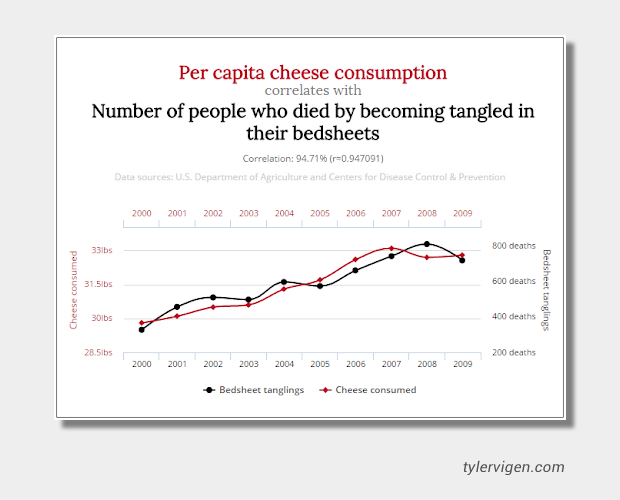

Even though the charts on the site show a strong correlation between the end of the gold standard and a variety of different things, that doesn’t prove it caused the issue. Correlation isn’t causation: For example the number of films Nicolas Cage appeared in between 1999 and 2009 strongly correlates with the number of people who drowned by falling into a pool during the same period. The increase in per capita cheese consumption between 2000 and 2009 almost perfectly matches the number of people who died by becoming tangled in their bedsheets.

Collin concedes that some of the charts may simply show a correlation.

“We get a lot of people who think that we’re attributing things to the end of Bretton Woods that we shouldn’t be,” says Collin. “And maybe in a little way, sometimes we do, because to be completely honest, the website is a meme. We embrace that. We love that. That’s what’s made it so popular and anytime we find any chart that has an unusual inflection point in 1971, you better believe it’s going on there,” he says.

Prentice adds: “We just put a bunch of data on a website and asked a question, right? So we’ve tried to not like explain all those charts on the website. We just want it to exist and let people answer their own questions and let them debate among themselves.”

And of course other things happened in 1971: Disney World opened, the Monkees broke up. Could these things help explain why that year changed everything?

“The one that we see the most is that someone says ‘I was born that year. This was all my fault’,” says Collin.

A more serious attempt to explain the major economic changes the charts show, is to attribute them to the wave of deregulation that swept over advanced economies in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Prentice says that he’d wrestled with this because from his libertarian, anarcho-capitalist influenced world view, everything should have become so much better.

“Why did everything get worse after deregulation?” he asks.

This is a great question to ask. (It’s) because the money system is so broken — it’s not capitalism. This is not what we’re advocating for. You took monetary socialism and then you took the reins off of it.

“So yeah, everything got way worse and the inequality got way worse. From that lens I think it’s much clearer to see why deregulation actually exacerbated everything.”

And while we’re trying to poke holes in the theory, a bunch of stuff has also got way better since 1971. Life expectancy in the U.S. is up 10%, infant survival rates have increased 71%, the food supply per person is up 21%. Globally, things have improved out of sight: in the early 1970’s half the world’s population lived in extreme poverty, now only 10% do. The number of illiterate people has dropped by more than 50%, while the number of people worldwide who live in a democracy grew from 32% to almost 56%

Prentice believes technological progress is the reason these some things have improved.

“We can afford more cool gadgets to increase our productivity, even something like as simple as the washing machine,” he says. “We used to spend hours a day washing our clothes and hanging them up and drying them. Now I don’t even think about it. Technology improves things like crops, right? Look at all the agricultural gear that we use now, these giant harvesters and all these things that allow us to get our food cheaper. In general, I believe all of the things you just listed are due to deflationary pressure inside an inflationary system.”

So essentially he’s saying that all of the things that got better, would have performed even better if they hadn’t been hampered by the end of the Bretton Woods system.

Economics backgrounds

Prentice says the pair are well aware their ideas are outside of conventional economic thinking, but say that’s because they’ve attempted to approach things from first principles and “expose the errors that other economists make.”

“We’ve seen their arguments, and we constantly question ourselves,” he says. “It’s like at the end of Marty Bent’s podcasts, he’s constantly saying ‘Are we crazy?’ We ask ourselves that all the time. I don’t have any hubris that I am a smarter economist than anybody else. But I do know that I work from logic and first principles, and I do wish to benefit everybody in the world.”

Since June they’ve also been expounding on their ideas in a newsletter, which is up to issue 68 already and hits inboxes every couple of days.

“We started the newsletter to give these little economic tidbits and explain little bits of monetary history because we believe that Bitcoin is inevitable and it is the best money that has ever existed,” says Prentice.

Collin says it may one day prove to be the first draft of a book on the topic.

“If our audience continues to grow, and we continue to get a good reception, we’re building up a library of content that may one day be edited into a book,” he says. “An ebook with a more cohesive analysis of monetary history and the emergence of a new paradigm, which is Bitcoin — which will change the world because it is here and it can’t be stopped.”

Andrew Fenton

Buterin’s ETH treasury warning, Bitcoin $250K a ‘maybe’: Hodler’s Digest, Aug. 3 – 9