Author Neal Stephenson famously invented the term “Metaverse” with the publication of Snow Crash in 1992 — a year before the World Wide Web or Doom even launched. But for crypto fans, his fictional depictions of early versions of Bitcoin more than a decade before it was invented are even better reasons to celebrate his work.

In his 1995 novel The Diamond Age he described an anonymous peer-to-peer communication system that could transfer money. A short story he published in TIME that same year called The Great Simoleon Caper explored a private, cryptographic digital currency using private keys called CryptoCredits.

His most in-depth work detailing a plan to set up money outside of the control of the state was the 1999 doorstopper opus Cryptonomicon, whose title was partly inspired by the Cyphernomicon FAQ.

Stephenson was so influential among the cypherpunks that some believe the Bitcoin White Paper was deliberately released on his birthday, October 31, in honor of his work.

Others have even suggested — only half jokingly — that he might be Satoshi himself. Reason Magazine put out an article in 2019 saying he probably wasn’t, but it wouldn’t be that surprising if he was.

“It’s plausible that Neal Stephenson invented, or helped invent, Bitcoin, because that is simply the sort of thing that Neal Stephenson might do,” wrote Peter Suderman in the piece.

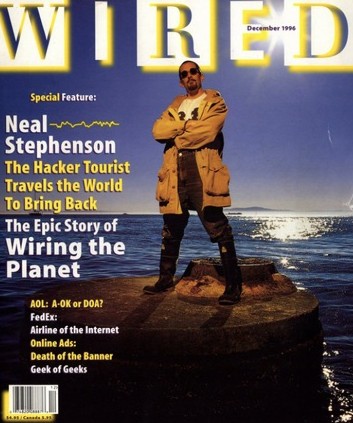

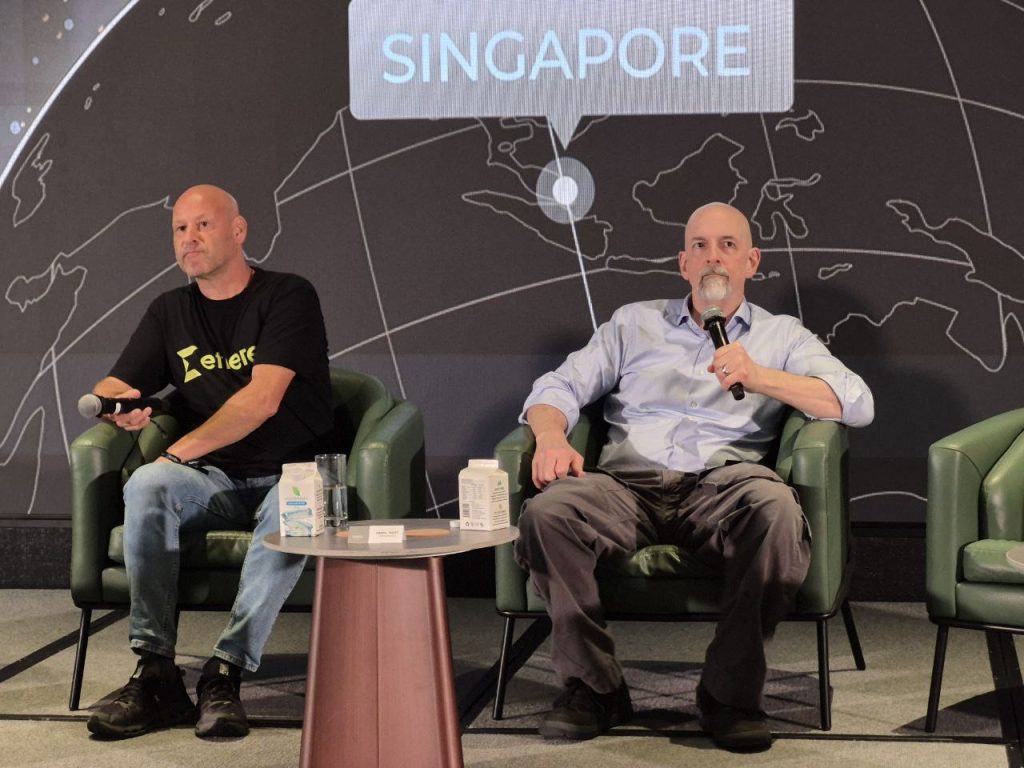

Stephenson tells Magazine during an interview in Singapore he’s been fascinated by codes and cyphers since he was a kid in the 1960s.

“I was a little code-breaking geek when I was a little boy,” he says in his thoughtful drawl.“On the dust flap of the original edition [of Cryptonomicon] there’s a picture that my Mom or Dad took for me when I was probably eight years old, lying on a couch reading a book about code.”

Hanging out with Habitat’s cypherpunks

Cryptonomicon came about partly due to the success of Snowcrash. In the mid-1990s he began hanging out with the cypherpunk devs behind an early proto-Metaverse called Habitat. They’d politely let him know they independently coined the term ‘avatar’ some years before Stephenson used it judiciously in the book.

Created by LucasFilm in the mid-1980s for Commodore 64s on dial-up, it was later acquired by Fujitsu and released for free on the web.

“It was an interesting combination of cultures,” says Stephenson. “It was both hippie west coast Berkeley, and at the same time, you know, very strong libertarian, anti-central authority, owning guns, being ready to defend yourself, kind of mentality.”

A core issue with having other people’s avatars come into your virtual space is working out a safe way to run “code from random strangers on the internet,” which Stephenson describes as “a crypto problem all the way.”

He says these Bay Area cypherpunks were initially focused on privacy and decentralized power, “and then at one point I came down and suddenly they were all talking about money,” he says.

“A whole world sprang up around finding ways to do monetary systems that were independent of government. But this was all pre-blockchain, okay? So none of that had been invented yet.”

Bitcoin without blockchainin Cryptonomicon

Intrigued by the idea, Stephenson set about imagining how it might happen, in page after page of comprehensively researched and credible detail — just as his recent Terminal Shock novel imagines how geoengineering to stop climate change might happen in practice.

Cryptonomicon is a techno-thriller that traces the history of cryptography, from Alan Turing and the Bletchley Park crew that broke the Nazi’s Enigma code in WW2, to their modern-day descendants who try to build uncensorable, privacy-preserving electronic money.

The e-money in the novel explicitly references digital gold, uses public key cryptography, digital signatures and fulfils the cypherpunk aim of establishing money outside the control of the state and banks.

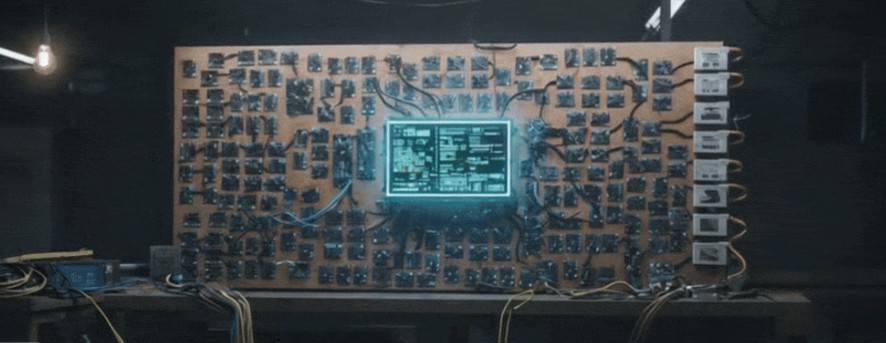

The key difference is that in the absence of blockchain, the solution he settled on was to host the system in a hardened offshore data center in the fictional Sultanate of Kinakuta.

Stephenson says this was inspired by various cypherpunk plans to run e-money out of libertarian jurisdictions such as North Sea seasteading platform Sealand or the island of Anguilla.

“It was some years later that blockchain was invented and made all of that stuff irrelevant, so no one needed to think in terms of having a server in a special room somewhere that was safe.”

In his book Zero to One, Peter Thiel said Cryptonomicon was required reading in the early days of Paypal, which may help explain David Sacks and Elon Musk’s interest in the topic.

Jack Dorsey, a member of the cypherpunk mailing list in the ‘90s, was also a major fan. Is it possible that Satoshi himself read or was inspired by the book?

“I mean, it’s possible,” Stephenson says, but downplays the idea, adding: “You don’t have to have read my book in order to be thinking about those things.”

Stephenson used to know everything about crypto

Stephenson has a vast intellect. He becomes obsessed with learning everything there is to know about one highly technical subject at a time, across engineering, technology or history.

Then he writes an insanely detailed, ambitious, often quite sprawling novel about it, and moves on.

Obsessed with space flight, he became an early employee at Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin in 2006. He transformed his knowledge of orbital mechanics and the Kessler Syndrome into the brilliant near-future epic Seveneves, detailing how humanity might escape from Earth into space if required by a planetary emergency. Bill Gates hailed it as one of the books of the year and praised its scientific accuracy.

“The way it works in my business, is that when you’re working on a book, you get very involved with any source of information that you can,” he says.

“Right now, I know a lot about deuterium” — a key component in hydrogen bombs and fusion reactions — “because that’s the subject of the book I just finished. And if you talked to me two years ago, I would have known a lot about American communism in the 1930s.”

The US communism book is called Polostan, and the novel featuring deuterium is Polostan’suntitled sequel due out in 2026.

Stephenson says there’s not enough room in his brain for everything he learns to find a permanent home.

“Whatever I knew about crypto and cypherpunks in 1999 got replaced by, you know, what kind of periwigs did a British gentleman wear on the street in 1683 [which he researched for the Baroque Cycle] so it’s falling out of your head. You can’t just keep tracking this stuff forever.”

“When Bitcoin did come around some years later, it was, you know, a surprise to me. It was a new idea to me. And a lot of people were surprised that I was surprised.”

Stephenson is among fewer than 1M people in the world with 1 Bitcoin

That said, Stephenson is a wholecoiner, putting him in a club with fewer than 1 million people worldwide.

“I ran into someone who was appalled that I didn’t have a Bitcoin, and who gave me a Bitcoin when it was $260, or something like that,” he says. He says he still has it, though lost a couple of sats moving it to a better wallet than his phone.

The person who gave it to him was likely “Bitcoin Jesus” Roger Ver, who posted about helping Stephenson set up his first wallet in 2013. Unfortunately, by the time Magazine met Ver in 2019, he was only gifting people $20 worth of Bitcoin Cash.

Metaverse pulls Stephenson back to crypto

After a break of about two decades, Stephenson was pulled firmly back into the crypto world in 2022, after the Metaverse became the hottest narrative of the cycle. He co-founded Lamina1 with the aim of creating tools that could help build a decentralized metaverse, in contrast to the corporate vision of Meta.

The key to this is working out an economic system that rewards a diverse array of people for their contributions to building the Metaverse. Lamina1’s Spaces protocol is a way to launch crowdsourced projects and track the contributions of writers, designers, animators and developers to pay them via blockchain.

“The idea with what we’re doing with Spaces and so on, is to create a way that the artists who aren’t necessarily technically inclined and who don’t ideologically care about crypto …. can still benefit from what blockchain technology has to offer,” he says.

A meeting with Ethereum cofounder and Snow Crash fan Joe Lubin at ETH Denver in February as “part of the ongoing quest for financing” saw Spaces expand to the Consensys L2 Linea with the Stephenson-created Artefact set to showcase the platform.

Given his track record in predicting the future years before it comes to pass, let’s hope he’s missed the mark with Artefact — a game he’s written a series of world-building short stories about that he’s toying with turning into a novel.

It’s about a future where the AI singularity occurs — called The Spike — and the major AI systems immediately begin to battle each other for resources and territory, decimating the human population.

Stephenson says he realized that everything in the natural world has to compete to survive, but AI has been protected from fighting for survival so far.

“So the idea was: What if you did make them compete,” he says. “What if you get them to believe that the other big AIs were direct threats to their existence?”

The post-Spike world is dominated by a dozen AIs called Bigs, each located in a different physical data center from Cairo to Tibet. The gameplay combines elements of resource management and trading card games. It follows a scavenger on one of the fringes of the few remaining human groups as they make their way through the apocalyptic landscape.

It’s not crowdsourced, however, and is being developed in-house at Lamina1 with partners like Avatar VFX house Weta Workshop providing the visuals. Revenue will come from trading fees on NFT ‘Artefacts’ and subscriptions.

Stephenson explains Artefact may feature crowdsourced elements in the future, but is mostly designed to showcase what the infrastructure can do.

“Some people call it ‘dogfooding’. Another term is ‘dining at our own fine restaurant’.”

The trouble with crypto

Although Stephenson has been writing about crypto since Vitalik Buterin was in diapers (literally) and now heads up a crypto project with its own cryptocurrency, you can sense a faint whiff of distaste about how the industry has developed.

He chooses his words carefully when Magazine asks about this.

“There is a tendency culturally within the crypto world to immediately jump to a financialized way of thinking about everything, and so any new development that happens immediately gets reduced to some kind of financial goal,” he says.

From the perspective of game developers, that means designing games to make money, rather than games that provide value to players using creativity and imagination.Stephenson says his co-founder Rebecca Barkin says you can’t reverse engineer a compelling experience backwards from a desired financial outcome.

“A lot of the suspicion that crypto is viewed in creative communities arises from that, and if there’s something that we have to contribute here, it’s maybe an approach that isn’t so quick to jump immediately to financialization.”

Andrew Fenton

Is the cryptocurrency epicenter moving away from East Asia?

East Asia has experienced a major decline in crypto adoption over the past year when compared with other regions.

Read moreMati Greenspan’s boss bribed him with 1 BTC to join Twitter: Hall of Flame

Quantum Economics founder Mati Greenspan signed up for Twitter and got into Bitcoin on the same day back in 2012.

Read moreWeb3 games shuttered, Axie Infinity founder warns more will ‘die’: Web3 Gamer