|

|

Coinbase is facing a flurry of lawsuits after disclosing a data breach that compromised nearly 70,000 customer accounts, with estimated losses reaching as high as $400 million.

The exchange says overseas customer support agents were bribed into helping scammers gain unauthorized access to user data in December. The company disclosed the attack to the public in May.

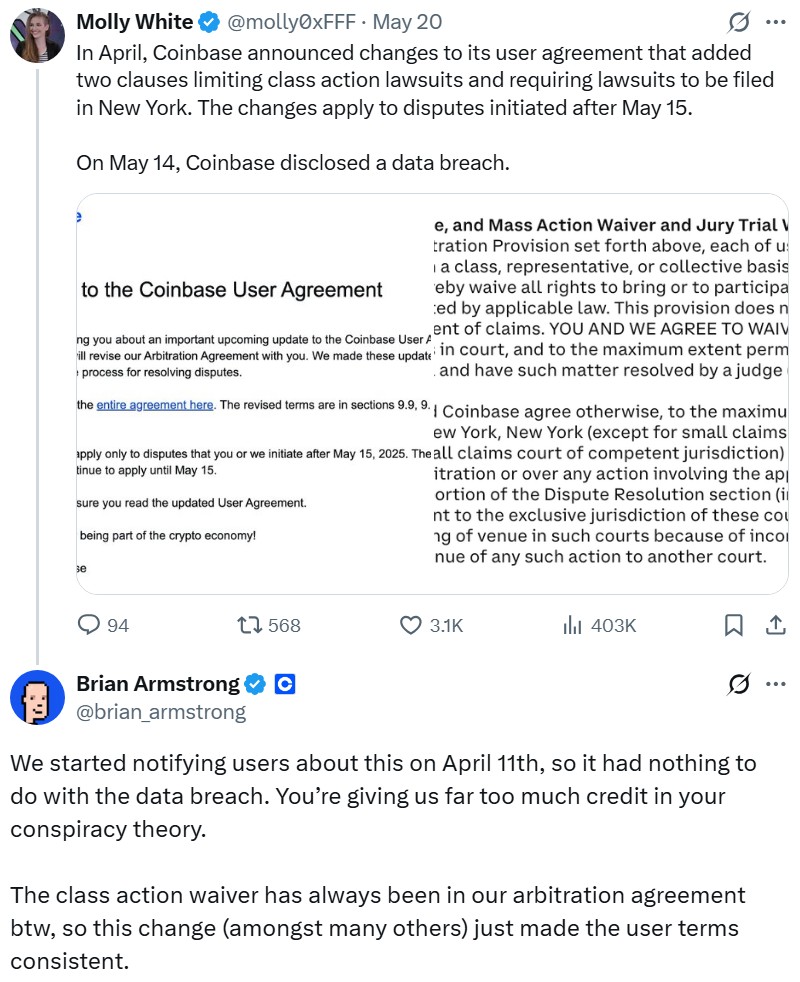

There were some reports that Coinbase had updated its user agreement just before announcing the breach, with critics accusing the company of adding an arbitration clause that limits class actions. Coinbase maintains that a class action waiver has long been part of its terms.

Charlyn Ho, founder and CEO of the law and consulting firm Rikka, says such clauses are standard in the US, where user agreements are typically enforceable. But those terms and conditions may not hold the same weight in other jurisdictions.

To understand the legal obligations crypto exchanges face when handling sensitive data, Magazine spoke with Ho in the US, Catherine Smirnova of Digital & Analogue Partners in Europe and Joshua Chu of the Hong Kong Web3 Association.

The discussion has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Magazine: Is there a federal law in the US that defines or governs data breaches?

Ho: What actually is a breach is not legally uniformly agreed upon, but in the layperson’s mind, any kind of revelation or unauthorized access of data is a breach.

We do not have a federal data breach statute. We have 50 states that all have their individual breach notification rules. The Coinbase one was notified in Maine.

There are overlapping rules. For example, if you’re a publicly traded company you’re subject to the Securities and Exchange Commission’s jurisdiction. The cybersecurity regulations that recently went into effect require disclosures to investors or shareholders on an 8-K within certain time frames. We don’t have a singular GDPR-esque statute.

Magazine: Who should be held responsible when a crypto platform is breached?

Ho: In the US, we have almost complete freedom of contract. Generally, contracts are held to be enforceable unless it’s unconscionable or there’s an extreme imbalance of power — like an adult and a child. But in general, the courts in the US will respect consenting adults who have an opportunity to read these terms.

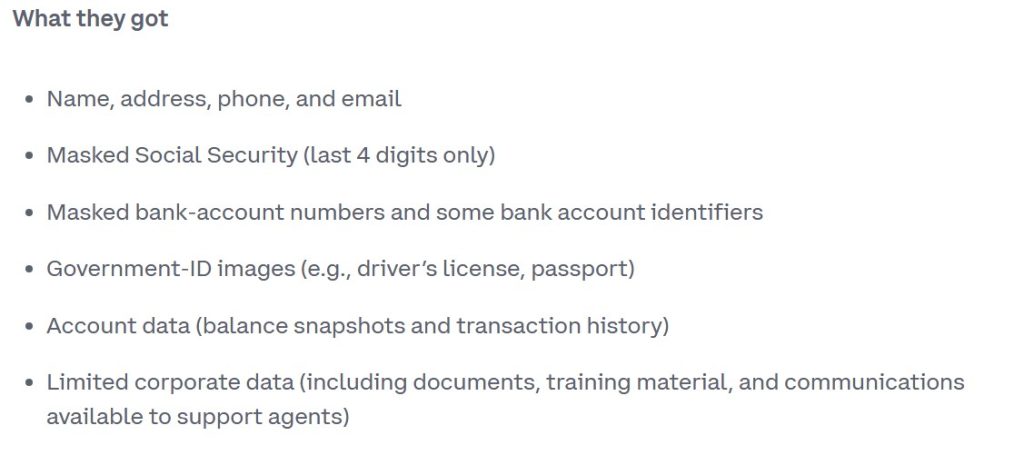

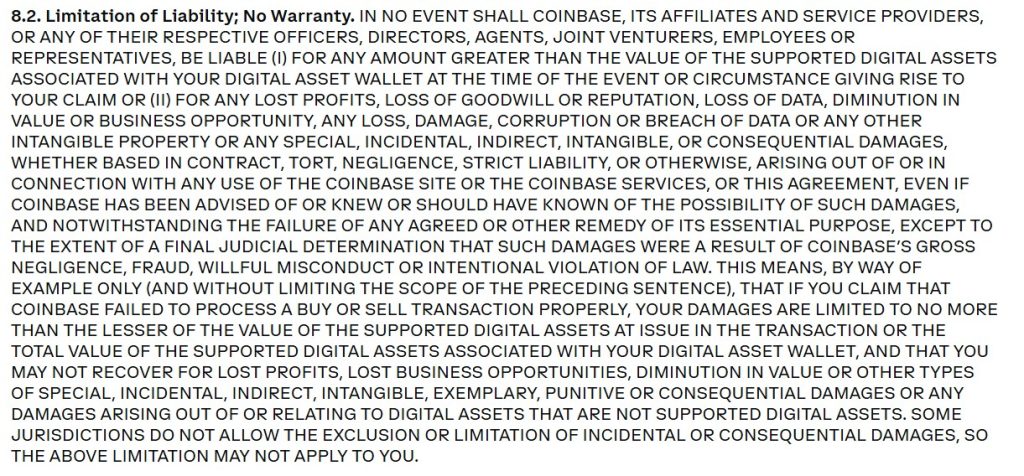

If you look at Coinbase’s terms, there’s a limitation of liability that basically says it won’t be liable for lost profits, loss of data or any loss, damage, corruption or breach of data.

When you click through it, you accept these terms. As long as the consent was valid, then you’re bound by them. Unfortunately, a lot of consumers will find that they’re not going to be able to recover a lot. Coinbase did say that they will reimburse people that were scammed. Coinbase is doing that out of their desire to have good relationships with their customers. But legally speaking, they don’t have to do that.

Magazine: How will this be treated outside of the US?

Chu (HK): The data owner or the party that has custody of the data will usually be held responsible, though it depends on the locality of the user in question.

As a litigation lawyer, I can say that regardless of whether something is written into a contract, many issues can still be argued in court. There are legal limits to what a company can carve out through its terms and conditions. You’ll often see language like ‘to the maximum extent permitted by applicable law’ in user agreements. Some of these carve-outs simply don’t hold up.

Take the GDPR [legislation in Europe] for example. Its legal scope is mandatory. When it comes to processing the personal data of EU residents, it doesn’t matter what a contract says. GDPR is regulatory, not contractual, which means businesses can’t use their terms and conditions to override or exclude those obligations.

Smirnova (EU): What really stands out in Europe is that regulation is layered. Crypto exchanges aren’t only bound by sector-specific laws — they’re also subject to GDPR, consumer protection laws and broader EU regulations like the single market framework.

All of these rules still apply to crypto exchanges. Consumer protection laws, for example, protect users even if they’ve agreed to certain risks. If someone buys Bitcoin expecting it to rise but it doesn’t, the exchange isn’t liable — that’s a fair market loss. But in the case of a data breach, it doesn’t matter what the terms and conditions say — the exchange is still liable.

Magazine: What are the legal and regulatory implications of how crypto exchanges conduct KYC and store user data?

Smirnova: When we talk about platforms like Binance, Kraken or Coinbase, I refer to them as Web2.5 companies. These platforms still store data centrally and operate in a centralized way. There’s no good reason they should be exempt from the regulations that apply to traditional Web2 platforms.

Why do they store user data centrally when decentralized options exist? Because they don’t want to decentralize. Data is an enormous competitive advantage. These companies want user data to predict demand, personalize services and expand their market reach. They’re leveraging that data commercially, and so, they should be held responsible if it gets compromised in a data breach.

If you’re holding and monetizing centralized user data, then you should be held liable like any other centralized entity.

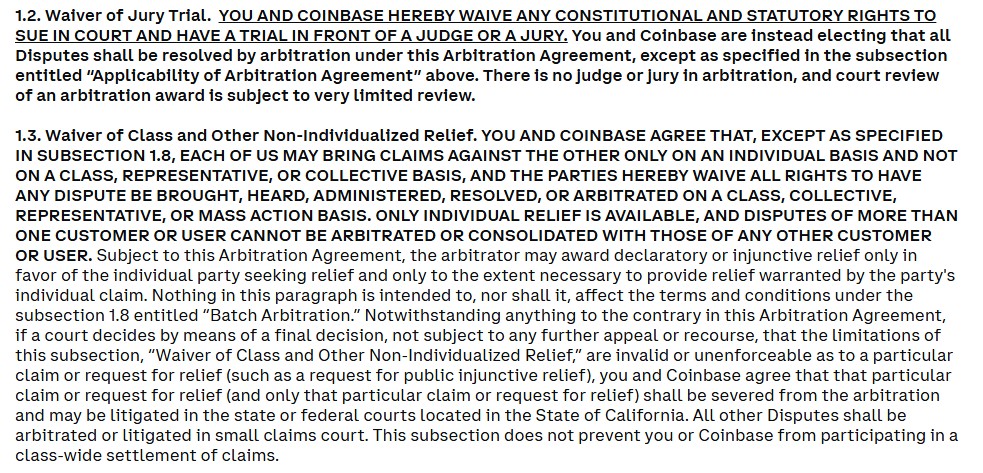

Magazine: Should crypto platforms be allowed to force users into private arbitration even in cases of a serious data breach?

Ho: It is interesting if they literally made the change right before announcing this breach, but I would be surprised if they didn’t already have an arbitration clause beforehand; there were already references in other parts that were not amended to arbitration. That’s already best practice in most terms of service for consumers. The reason why large companies prefer arbitration and class action waivers is because they want their disputes to be private. In arbitration, it’s private; in litigation, it’s public.

There was a Supreme Court case in 2011 called AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion. Essentially, the Supreme Court overruled a Ninth Circuit ruling based on California contract law. Basically, some consumers had a contract with AT&T that had a Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) requirement. The Ninth Circuit ruled in favor of the consumers: that the FAA requirement to have binding arbitration was not permissible under California law. The Supreme Court found that federal law preempted California law.

The bottom line is that the Supreme Court has ruled in a number of different cases that the FAA preempts any state laws that may ban or restrict class action waivers or arbitration clauses in user agreements.

It’s pretty unlikely that this arbitration requirement is considered not enforceable. The only question is whether Coinbase was being sketchy by rolling it out right before a data breach announcement. But again, I would hazard a guess that it was already there and maybe they just added some sections to make it clearer.

Chu: We often use Binance as a classic example of how crypto platforms design their dispute resolution clauses to protect themselves. They include a number of robust provisions that make it extremely difficult to litigate or arbitrate against them. This includes jurisdiction clauses, short limitation periods and fallback language.

Binance selects Hong Kong as the centralized location for arbitration in user disputes. That choice is subject to challenge, of course, but it’s clearly strategic. As someone who’s acted as counsel in Hong Kong arbitration, I wouldn’t say the process is difficult — if anything, it’s quite efficient. Hong Kong courts are quite advanced in terms of digital infrastructure. That said, arbitration is not cheap. You have to pay arbitrators’ fees and your own legal counsel. It adds up quickly.

One of the biggest barriers is the way Binance frames its dispute resolution terms. For instance, they require you to initiate arbitration within six months of a transaction. That’s a very tight deadline. Once you clear the hurdle of the limitation period, you’re still facing the cost of private arbitration.

Magazine: How is privacy and data evolving?

Smirnova: We can see that our data is used by thousands of digital platforms. We enjoy this because we live in an era of hyper-personalization. We want to receive tailor-made content or special offers that are actually relevant to us. It’s possible because of the analysis of our private data.

But on the other hand, we’re finally starting to understand its value. I believe we’re realizing this too late. If Big Tech makes billions off our data, then why don’t we participate in that profit? This is the key question for the next decade, because our data will be used in even more ways — especially with the rise of AI. Just look at Meta, which recently announced it will train AI systems using public data in the EU.

We can’t hide our personal data anymore. Governments collect our biometrics, and we give companies like Apple access to our fingerprints, our face scans, even our eyeballs. Maybe it’s time to accept that and move to the next step: rethink monetization.

That will only happen if society becomes more and more conscious about how we use and share data. That’s how we can start changing the rules of the game.

Yohan Yun

The value of a legacy: Hunting down Satoshi’s Bitcoin

Satoshi’s fortune continues to intrigue — here’s what we know about Bitcoin’s founder’s role in the early days of the blockchain’s existence and their unmoved BTC holdings.

Read moreSEC seeks appeal over Ripple, crypto prices plunge and EU debuts Bitcoin ETF: Hodler’s Digest, Aug. 13-19

SEC files motion for appeal on Ripple’s case, Bitcoin and Ether prices plunge and Europe welcomes first spot Bitcoin ETF.

Read moreWeb3 games shuttered, Axie Infinity founder warns more will ‘die’: Web3 Gamer