|

|

Crypto firms are no longer just challenging the traditional financial system — they are increasingly becoming part of it.

Companies like Circle and BitGo are reportedly pursuing banking charters and preparing for a wave of incoming stablecoin legislation that could further blur the lines between crypto firms and traditional banks.

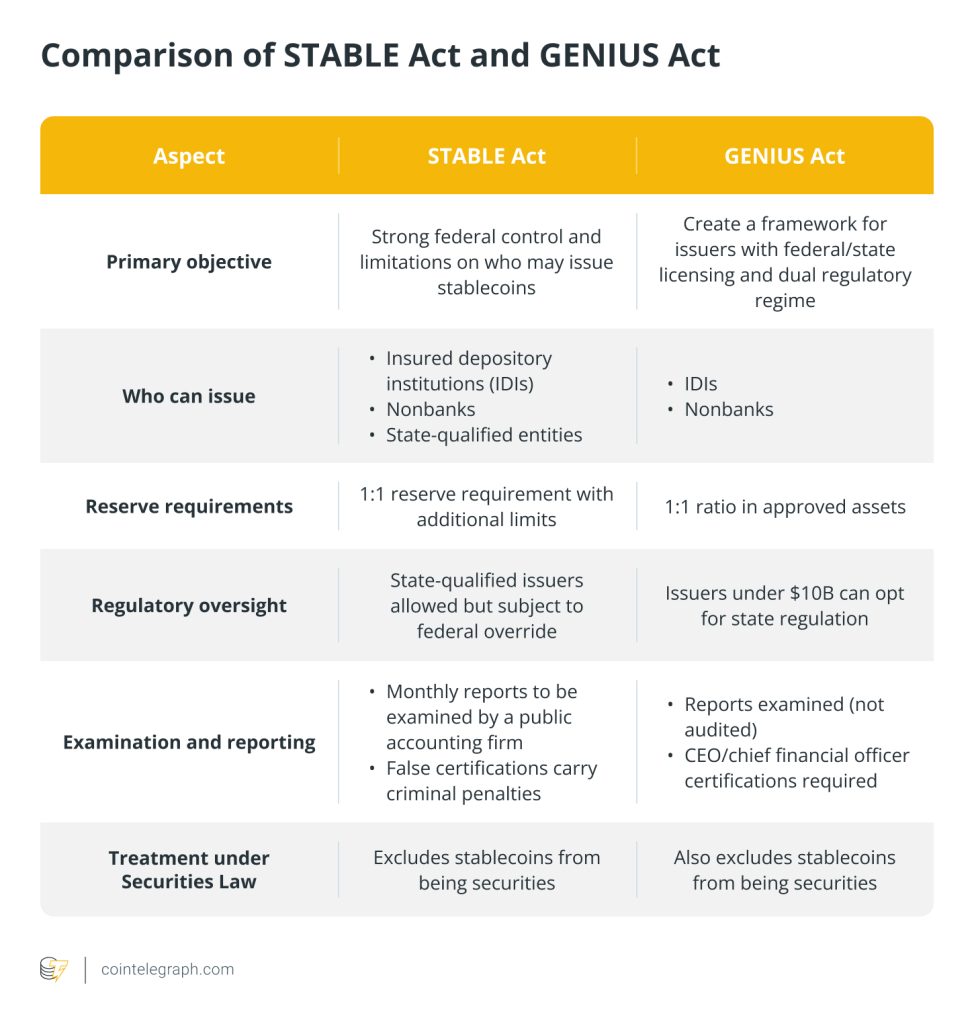

In the US, two major bills — the Stablecoin Transparency and Accountability for a Better Ledger Economy (STABLE) Act and the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins (GENIUS) Act — aim to introduce new rules on stablecoin issuers, covering everything from reserve requirements to licensing and compliance obligations.

Europe’s Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) framework alreadyregulates stablecoins,and in Hong Kong, a proposal would require stablecoin issuers to obtain a license from the Hong Kong Monetary Authority.

To discuss to ramifications, Magazine brought together legal experts from across the globe: Charlyn Ho of Rikka in the US, Joshua Chu, co-chair of the Hong Kong Web3 Association, and Yuriy Brisov and CBDC and market researcher Alexandra Zviagintseva, both from Digital & Analogue Partners in Europe.

Magazine: In what way does becoming a regulated bank change how a crypto firm operates?

Chu (HK): Obtaining a banking license would give firms a degree of trust and allow them to offer traditional banking services like deposit-taking and lending. With a bank charter also comes regulatory oversight, including capital control requirements, KYC/AML obligations, and regular audits.

The idea of large crypto players seeking banking licenses is actually not a new development. Back in 2017, Switzerland had at that time invited major crypto institutions to come to the jurisdiction and consider obtaining a banking license. Even then, banks had a role to play. On-ramping and off-ramping currencies are a huge part of the process, whether you like fiat or not. One of the early frustrations among crypto players was seeing money or wealth they couldn’t really touch, because the moment they tried to cash it in, they were red-flagged by banks due to AML policies around unusual or irregular transactions.

Ho (US): When I was at my old law firm, one of the early pro bono projects we worked on involved helping women in Afghanistan who were traditionally barred from having bank accounts. The goal was to use Bitcoin to give them access to funds in a way that couldn’t be taken away by male family members. In contrast, traditional banks in some places might impose restrictions like requiring a male co-signer for account creation or withdrawals. So crypto offered an alternative system that could provide banking-like access without traditional barriers.

I don’t necessarily think that crypto firms getting banking charters means they will abandon all of those original ideals. But the mainstreaming of digital assets does mean some loss of independence from the traditional banking system. If the GENIUS and STABLE Acts (or any future regulations) pass, they will effectively create a regulatory framework for crypto companies that mirrors the framework for traditional finance and banking.

Magazine: Are banks pushing back against stablecoins, and is that making stablecoin firms act more like banks?

Brisov (EU): Initially, banks resisted stablecoins due to competitive concerns. But as it became clear that stablecoins are here to stay, banks have been the first to pivot. In Europe, several banks have already applied to issue their own stablecoins. Similarly, in the US, Bank of America and others have indicated interest.

From early on, one approach was to use crypto as a technology, while still viewing it as part of the global financial system. Players like Circle and Coinbase followed this path, adhering to regulations and rules from the outset.

Kraken was the first crypto exchange to apply for a bank charter in Wyoming. Wyoming is well known among crypto enthusiasts, and in 2020, it created a new entity called a Special Purpose Depository Institution (SPDI). Kraken became the first SPDI in Wyoming. They stated on their website that they received a bank charter. But it wasn’t a federal bank charter or even a traditional state bank charter. It was a special-purpose solution allowing crypto companies to receive deposits, custody cryptocurrency, and facilitate crypto exchanges.

So I wouldn’t say crypto is simply being pushed into the global financial system, but it’s more that certain players chose that path from early on.

For example, Circle has consistently been pro-regulation. They began publishing attestation reports even before frameworks like MiCA in Europe. It was already acting like a bank or bank-like institution.

Magazine: What are the key procedural hurdles both the STABLE and GENIUS Acts would have to overcome to become law?

Ho: GENIUS and STABLE are parallel legislative proposals, and neither is law yet. From what I understand, the STABLE Act would create more of a federal regulatory regime, giving stronger control to the federal government. The GENIUS Act leans more toward a state-focused regulatory framework. Overall, both acts are designed to create more clarity.

The process in the US is that you generally have a sponsor. Generally speaking, a bill has to pass both houses: the House of Representatives and the Senate. If it does, it then goes to the president for either a signature or a veto.

Magazine: How likely is either bill to advance beyond committee?

Ho: I think one or the other will advance. This is just my own opinion: since they have overlapping scopes, either they will need to be de-conflicted so there aren’t contradictory legal requirements, or one of the two will have to be passed.

Brisov: This STABLE and GENIUS proposal in the US essentially mirrors much of what MiCA has already done. MiCA applies across 27 EU member states; the US has 50 states, but the framework is quite comparable. While MiCA is a broader regulatory regime, STABLE and GENIUS are focused solely on stablecoins.

Under these US proposals, either a bank or a tech company could obtain a license or charter to issue stablecoins. They’ve also introduced thresholds — similar to MiCA. For instance, one of the bills states that if a stablecoin reaches $10 billion in turnover, it would then fall under dual regulation by the Federal Reserve System.

At the state level, companies can begin receiving stablecoin licenses. If any of them grow large enough, the Federal Reserve would then likely oversee and regulate them. Importantly, like MiCA, stablecoin issuers won’t be allowed to pay interest on stablecoin holdings.

Ho: I think it’s important to recognize that, like other areas of US versus European law, there are fundamental differences. For example, I’m a privacy and cybersecurity specialist, and in privacy law, Europe’s GDPR creates a comprehensive framework for protecting personal data across the EU. In contrast, the US doesn’t have a federal privacy law yet — privacy is handled state by state, which mirrors GDPR somewhat, but only at the state level.

[The stablecoin bills] highlight another US-EU difference. In the US, there’s the potential for federal versus state regulatory conflict.

Magazine: And how does MiCA regulate stablecoins?

Brisov: MiCA states directly that if you issue Electronic Money Tokens (EMTs) or Asset-Referenced Tokens (ARTs) — all stablecoins fall into the EMT category — issuers must first obtain an electronic money issuance license in one of the EU member states. For example, Circle received its license in France in 2023.

The second step is to get a license for the token itself. Issuers must prove they have 100% reserves backing the tokens and comply with the stablecoin regulations. If a stablecoin user requests to exchange their tokens for fiat money, the issuer must honor that redemption.

USDC, for instance, has fully complied with these requirements, which is why it is allowed across all EU member states and even outside the EU when counterparties are dealing with European entities. Even if you are based outside the EU, but your counterparty is in Europe, you still have to follow MiCA rules.

That’s why major crypto exchanges had to adjust their operations around Tether (USDT) as well. If they didn’t, they could face fines or restrictions when operating with EU customers or companies interacting with EU markets.

Magazine: How are stablecoins viewed by Hong Kong regulators in the wake of their pro-crypto stance?

Chu: The stablecoin bill is coming on the heels of the stablecoin sandbox that was launched earlier. If you look at the virtual assets trading platform legislation, it started as a sandbox. Once there was sufficient supervisory experience, regulators moved to enact formal legislation. We’re seeing a similar approach now.

The upcoming stablecoin bill was introduced in December. It’s expected to be enacted soon, with consultations completed. It will require fiat-referenced stablecoins to obtain a license from the HKMA. The licensing regime will include requirements for reserve management, operational controls, marketing restrictions and consumer protection. The HKMA license will create a category of central bank-approved stablecoins that are not CBDCs. It’s important to differentiate the two. This provides a unique regulatory status and blend for these two types of products.

Magazine: How does Hong Kong’s stablecoin bill fare against MiCA?

Chu: The stablecoin bill had the advantage of observing what MiCA did in the EU. MiCA has been strongly criticized for prohibiting stablecoin issuers from offering interest or remuneration based on holding duration.

The Hong Kong regulatory approach appears to be much more flexible. Hong Kong’s focus is on maintaining monetary and financial stability and protecting investors, without an outright ban on yield-generating activities. This is considered critical by issuers like Tether.

If you think about it, it’s quite a homecoming, because Tether — the original stablecoin innovation — was actually founded by a team based in Hong Kong. So it’s fitting that the legislation reflects that heritage.

Magazine: Do central bank-licensed stablecoins have the potential to operate as de facto CBDCs?

Chu: If you look at CBDCs, you can look just across the border into mainland China, which has a strict ban on crypto but strong encouragement for CBDC development. Stablecoins are specifically designed to integrate with the Web3 crypto economy. That’s why we made the decision to differentiate the two: to position Hong Kong as a melting pot that can facilitate both sides.

We haven’t seen a lot of businesses reacting yet, but there are huge opportunities created by Hong Kong’s regulatory development that aren’t available elsewhere. China is a massive and important financial market, and it remains to be seen how that wealth can be accessed.

Now, the SFC has issued circulars making it clear that Hong Kong should not be used to circumvent PRC laws. For example, you can’t simply set up in Hong Kong to get mainland Chinese users to trade crypto.

Zviagintseva: From a consumer perspective, we can see that CBDCs are competing with stablecoins. Both are simply payment methods, and it doesn’t really matter whether it’s a central bank digital currency or a stablecoin — the key difference is the issuer and who you trust more.

Different countries are exploring different models. Some, like the US, are leaning more toward stablecoins. Europe and other developed economies are less enthusiastic about CBDCs, largely because they already have stable and efficient financial systems.

For these regions, the challenge is identifying compelling advantages, like consumer privacy. In Europe, one proposed benefit of CBDCs is anonymity and confidentiality, since many people are wary of sharing personal data with banks and governments. Europe is moving cautiously. Only in October 2025 are they expected to roll out their CBDC strategy, and even then it’s just an initial pilot stage.

The US has taken a clear stance that, at least in the near future, there will be no digital dollar. But even before this, progress was slow. While there were some exploratory efforts, they remained at an early stage.

Now, with that direction clarified, USDC and USDT could emerge as the de facto digital representations of the US dollar, since they can already be used as payment methods. This gives additional momentum to stablecoins.

Magazine: Anonymity is proposed as a benefit in Europe, but privacy has also been a key concern of CBDC opponents.

Zviagintseva: Consumers generally want safety and control over their data. They prefer not to share personal information with institutions. In that sense, CBDCs could offer an advantage over traditional electronic money handled through banks—by moving toward digital wallets and currencies that offer more individual control.

However, this raises concerns for governments, who don’t want to lose visibility over money flows. If too much of the monetary system becomes untraceable, it could weaken oversight. That’s why the EU is considering specific limitations, like “anonymity vouchers”—a capped amount of digital money that consumers can spend privately. The rest of their transactions would remain traceable.

Yohan Yun

Meet the onchain crypto detectives fighting crime better than the cops

Meet the crypto detectives who trace hacks and theft onchain. Some are professionals, others are keen enthusiasts who log on after work.

Read moreDanger signs for Bitcoin as retail abandons it to institutions: Sky Wee

Sky Wee, an influencer with 4M followers, worries about Bitcoin’s future: “The real risk isn’t institutions buying, it’s retail not buying.”

Read moreWeb3 games shuttered, Axie Infinity founder warns more will ‘die’: Web3 Gamer