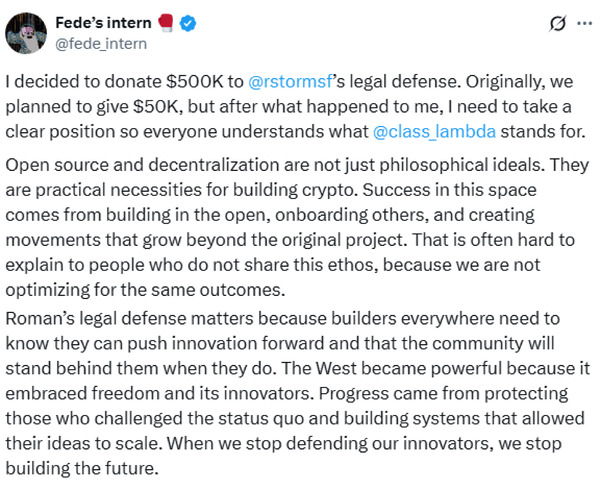

Roman Storm’s conviction over Tornado Cash has sparked a debate about whether US authorities are narrowing crypto privacy rights despite the White House’s recent report emphasizing the importance of self-custody and individual freedoms.

The case has drawn comparisons to earlier battles over Silk Road, raising questions about criminal intent, control of immutable smart contracts and whether privacy itself can ever outweigh security concerns. Meanwhile, the White House is pushing for a clear taxonomy of digital assets — commodity or security — highlighting how unresolved definitions and liability standards continue to shape US crypto policy discussions.

To explore the legal implications of Storm’s conviction and the broader policy context, Magazine spoke with Joshua Chu of the Hong Kong Web3 Association, Yuriy Brisov of UK law firm Digital & Analogue Partners and Charlyn Ho of US law firm Rikka.

The conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Magazine: Does Storm’s conviction highlight the tension between US policy recommendations on privacy rights and the way liability is assigned in crypto cases?

Chu: If I’m putting on my asset recovery lawyer hat, we always say we target the infrastructure to safeguard our clients’ interests. There are crypto mixers that argue the nature of their activity doesn’t automatically mean they’re always used for illicit purposes.

I do a lot of these cases, and I always say that it doesn’t matter if assets are going through centralized or decentralized platforms. Just because somebody purports that it’s a decentralized operating vehicle, it doesn’t mean you’re just publishing codes out there. At the end of the day, laws are laws. The real question is not whether we need new ones, but whether existing laws have been followed.

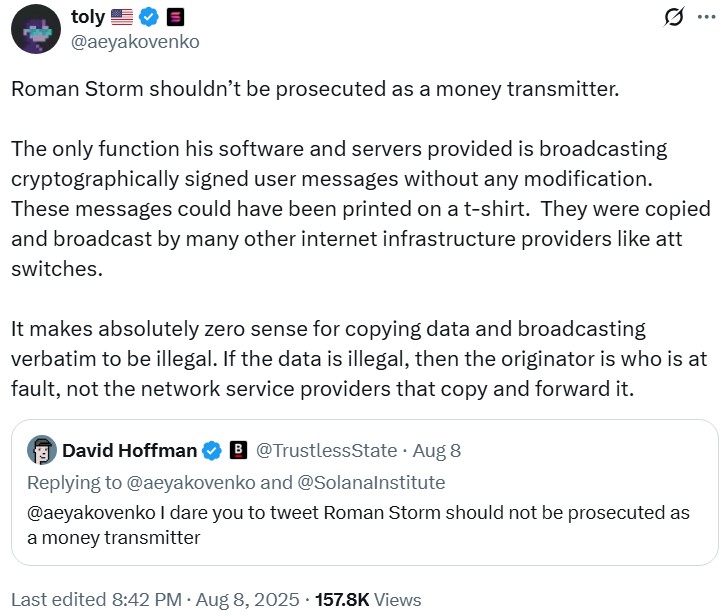

Brisov: I would also add to this discussion another case regarding Tornado Cash, which was Joseph Van Loon, et al. v. Department of the Treasury. It was a very important case where the court found that immutable smart contracts are not property and cannot be controlled by the people who created them if they’re a purely enforceable smart contract.

One important point is: If we can prove that no one controls the technology, then it isn’t property, which means no one can own it or be held liable for it. The Storm case with Tornado Cash is different. In the Howey case, the “economic reality” principle said we should look not just at the form of a transaction but at its actual economic structure. If you create something with malicious intent, that changes the analysis.

In US criminal law, liability depends on both actus reus (a guilty act) and mens rea (a guilty mind). If you design a tool to break the law, that shows criminal intent. The Silk Road case illustrates this: Ross Ulbricht argued that he wasn’t personally conducting illegal transactions, but the court found that by creating the platform with the intent for it to be used illegally, he was still liable.

Lack of control today doesn’t erase the criminal intent at the moment of creation.

Magazine: Do you agree with crypto advocates who criticize Storm’s conviction as an attack on privacy?

Ho: I don’t think it’s accurate to frame this conviction simply as an attack on privacy. Instead, it underscores this ongoing, unresolved tension, with different stakeholders falling at different points on the spectrum of how much privacy versus how much security is acceptable.

Crypto purists argue that the technology exists to reduce the power of centralized authorities by enabling self-custody and peer-to-peer transfers without intervention. But at the same time, major banks have begun adopting crypto in ways that run counter to that original philosophy. We see the same tension play out with Tornado Cash and even discussions around central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). Privacy is a key goal, but in practice, governments and courts have consistently taken the position that privacy cannot come at the expense of public safety.

A useful analogy is encryption. When encrypted messaging platforms like WhatsApp first appeared, or when Apple refused to unlock the San Bernardino shooter’s iPhone, the same arguments were raised: individual rights to encryption versus law enforcement’s need for access. Over time, courts and regulators have developed clearer boundaries around when communications can remain private and when law enforcement can compel access. That precedent may ultimately help guide how courts think about crypto privacy tools like Tornado Cash.

Magazine: With privacy now central to US crypto policy, are there any laws that directly protect crypto privacy today?

Ho: There isn’t a specific “crypto privacy law.” What we have instead are general privacy laws that can apply to crypto. For example, a wallet address would likely be considered personal information under the California Consumer Privacy Act. The definition of personal information there — similar to the EU — is broad: Essentially, any data that identifies or can be linked to a natural person.

This ties into the concepts of anonymous versus pseudonymous data. Anonymous data cannot be traced back to an individual, even when combined with other information. Pseudonymous data, on the other hand — like a wallet address — can often be connected back to a person when combined with enough other pieces of data.

So, while there isn’t a law written specifically for “crypto privacy,” there are binding privacy laws that absolutely apply to crypto-related information. In the US, the complexity is that it depends on factors like the type of information, how it’s collected, how it’s used and who is collecting it. The same wallet address might fall under different regulatory obligations if it’s being collected by a bank, a retail company or a healthcare provider.

Magazine: The White House report also recommended a ban on CBDCs, reiterating privacy concerns. How do different legal traditions shape the way countries approach stablecoins and CBDCs?

Chu: In the US, the debate is deeply tied to the common law tradition, which tends to be more favorable toward stablecoins. By contrast, civil law systems — particularly in continental Europe — lean more toward CBDCs. China’s legal system, for example, is heavily influenced by German law, which helps explain its position.

In China, we really have to think of two worlds. There’s the government-facing world, and then there’s the retail-facing world. China’s bans have always been aimed at its own citizens, preventing them from engaging in speculative economies. At the same time, they want to shield citizens from overindulgence in speculative assets while still engaging with global markets. That duality explains recent reports: Brokers in China are being told to stop offering stablecoin courses to the general public, while in Hong Kong, the government openly encourages development.

This reflects China’s long history of compartmentalized engagement with the outside world. In the 19th century, port city systems like Shanghai and Canton served as contained hubs for foreign trade. What we’re seeing now is a modern version of that same approach with crypto.

Magazine: What’s driving the White House’s focus on classifying digital assets into a clear taxonomy?

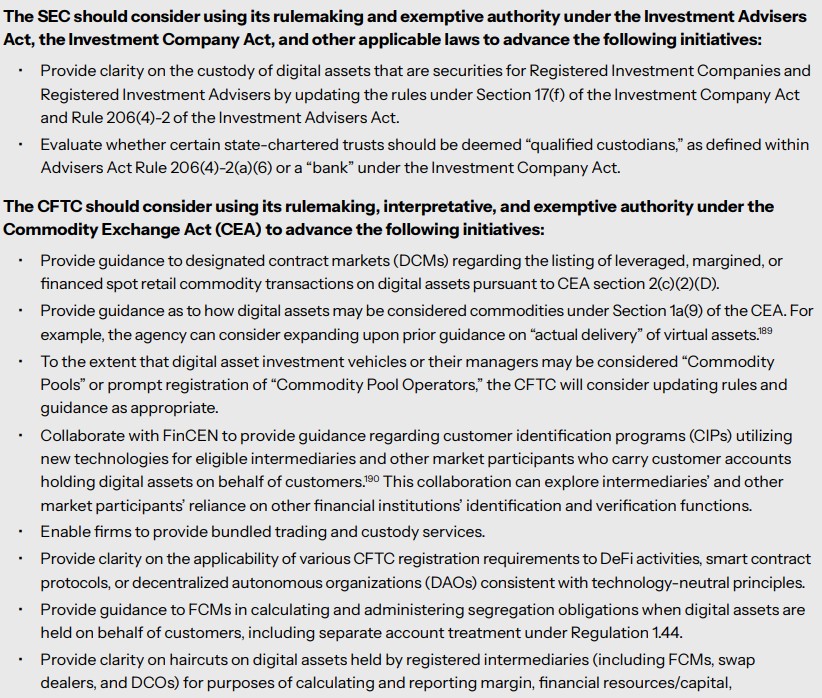

Ho: I think that’s kind of the crux of the issue is that there are commodities and securities under US law. The White House crypto report says that the current Internal Revenue Service guidance does not address whether a digital asset is considered a security or commodity for federal income tax purposes. It goes on to say that the code, which is the IRS code and case law, defines security in different ways for different tax purposes and also does not define the term commodity or defines it in a circular manner and does not cross-reference the commodities law meaning of the term.

So, there’s the commodities law, there’s the securities laws and then there’s tax laws. I think the issue is that none of these laws are harmonized. That’s sort of the point of the CLARITY Act proposal: to clarify when a digital asset is a security and when it’s a commodity because the scope of the Securities and Exchange Commission’s jurisdiction is that it’s the regulator for securities, whereas the Commodity Futures Trading Commission is the regulator for commodities. But if the central question of “What is a commodity?” versus “What is a security?” is confusing, then that naturally leads to tension between the two agencies.

The other complication is, remember we were talking about Judge Torres and how she, in her decision on the Ripple case, had made a comment that whether a digital asset is a security not only depends on the nature of the digital asset and how it is marketed, but also how it is sold. And so that adds even more complexity because that means it could be both, depending on different factors.

Magazine: Why is the discussion around the classification of digital assets as securities or commodities not echoed in other major crypto laws like MiCA?

Brisov: It’s actually pretty easy. The US falls under common law jurisdictions. Usually, in common law, it’s the precedent — the decision of courts or case law — that sets the legislation. In common law jurisdictions, there are not so many statutes because it’s easier to make laws step by step, changing gradually.

So, the securities laws in the US are very broad. If you read what a security is under the 1933 Securities Act, it’s a very long list. Anything that falls into this list can or cannot be a security, and it’s for the courts to decide. That’s why courts invent tests like the Howey test.

But in Europe, we don’t have this problem because Europe is a civil law jurisdiction. If it’s written in the law that this is a security, then it is. We have Markets in Crypto-Assets regulation now in Europe that regulates stablecoins and utility tokens. And there is Markets in Financial Instruments Directive that regulates all securities. So, you have to decide from the beginning whether you issue securities or utility tokens.

Of course, to some extent, there is a form test and an economic reality test, but it doesn’t apply as a law. It just applies for lawyers drafting papers. Otherwise, they will just be fined for issuing the wrong security offering. It’s much easier: You choose the way from the beginning, choose the legislation, file the paperwork and present it to the authority.

Yohan Yun

The ‘Polish Elon Musk’ and a 3D portal to the Metaverse

“We’re going to build the largest database of 3-D scanned people and objects in the world.”

Read more2026 is the year of pragmatic privacy in crypto: Canton, Zcash and more

The crypto industry has taken a sharp turn back towards privacy — and it can now exist side by side with regulatory compliance.

Read moreWeb3 games shuttered, Axie Infinity founder warns more will ‘die’: Web3 Gamer