Robinhood’s tokenized stock offerings in Europe have ignited debate over the legality of tokenizing equity, especially that of private companies like OpenAI.

OpenAI said Robinhood’s unapproved OpenAI tokens offer no equity ownership rights, causing regulators in Lithuania to open a formal inquiry. But that’s just the start. With concerns over how different jurisdictions approach tokenized shares, the boundary between innovation and illegality, and whether there are sufficient legal protections for stock token holders.

To unpack the legal complexities behind tokenized stocks, Magazine spoke with Yuriy Brisov of Digital & Analogue Partners, Joshua Chu of the Hong Kong Web3 Association and Yulia Murat, head of regulatory affairs at Global Ledger.

The conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Magazine: What is the legal foundation for tokenizing stocks, and how does it differ between public and private shares?

Brisov: Tokenization emerged as a technical solution — not a legal one. It’s simply a digital format for this existing brokerage structure. Usually, the voting rights are limited, but the economic rights are transferred to clients. This model is legal in the US and Europe.

The concern arises with private shares. If Robinhood only offered tokenized versions of publicly traded shares, there wouldn’t be many legal issues because the tokenized share is still the same share, just in a different format. In the US, a company can still issue paper share certificates signed by two officers, or go digital and issue them through a brokerage. A tokenized share is essentially a digital certificate.

Private shares, however, come with restrictions. You often need company or shareholder approval to resell. There are usually preemptive rights that require you to offer the share back to the company or other shareholders before selling it to outsiders.

Chu: This got headlines because OpenAI publicly condemned it. That’s because these synthetic wrappers are often created without understanding the rights attached to the original shares. Does the seller even have the right to offer this? If not, buyers may end up holding something that’s either worthless or comes with liabilities. If it breaches shareholder agreements, depending on the severity, it could have legal consequences.

Robinhood knew the risks. When they launched the tokenized shares, they said these are just synthetic representations. But if they’re profiting and using others’ trademarks, it opens the door to legal issues — not just securities law, but trademark infringement and broader compliance violations.

Magazine: When do tokenized shares cross the line into unregistered securities offerings?

Brisov: Robinhood and others are now saying they’re not reselling shares, but rather selling interests in shares. That’s a slippery slope that brings us to the Howey Test, which determines whether something is a security. If you invest money into a common enterprise expecting profits solely from others’ efforts, then it’s a security.

Most tokenized share offerings would likely fall under this definition. In both US and European law, what matters is the economic reality of the transaction, not what the documents say. If I’m buying a derivative of a stock, expecting profit and doing nothing else, that’s clearly a security.

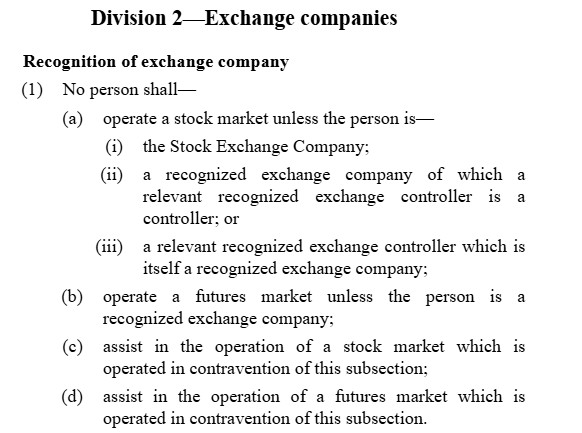

Chu: Under Section 19 of the Securities and Futures Ordinance (SFO) here in Hong Kong, it’s actually written into the law that the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong (HKEX) — which is a limited company — is the only entity that can deal with Hong Kong corporate shares.

You’re probably familiar with [American Depositary Receipts] — the mechanism allowing Americans to buy foreign company shares without directly going into foreign jurisdictions. You haven’t seen Hong Kong doing that a lot because of the monopoly provision under the SFO. If you do it and you’re successful, you’re likely to face litigation not just from regulators, but from the stock exchange itself. If HKEX wants to issue or list tokenized shares, they can. The law doesn’t prohibit using technology to record share ownership differently.

But we haven’t even touched on private companies, which is what Robinhood’s case is about. In this particular case, you’re looking at a synthetic relationship. You’re basically buying a beneficial interest, but not the actual underlying interest. That means you can’t sue if there’s an event where legal standing is required to go after an entity.

Magazine: What are the risks involved in issuing tokenized stocks through offshore entities?

Murat: When tokenized stocks are issued by offshore entities and sold to individuals in jurisdictions like the US, UK or EU, significant challenges arise from an Anti-Money Laundering (AML) perspective. These challenges stem primarily from differences in regulatory standards and difficulties in enforcing compliance across borders.

Another core challenge lies in the opaque ownership structures commonly used in offshore tokenization schemes. Tokenized shares may be issued through shell companies or special-purpose vehicles (SPVs) registered in secrecy jurisdictions, with no clear ultimate beneficial owner (UBO) disclosed. This lack of transparency conflicts with the regulatory expectations in the US, UK and EU, where UBO identification is a cornerstone of AML compliance.

When offshore platforms obscure either the identity of the issuer or the investor, they frustrate AML enforcement and hinder regulators’ ability to detect and respond to suspicious activity.

Magazine: Are there any legal and compliant paths to offering tokenized stocks to the public?

Brisov: If the company whose shares are being tokenized gives permission, there are two paths: either sell it privately to a limited group of investors or go public.

Under US law, you can make a secondary private offering via an over-the-counter deal if you’re a licensed broker-dealer. But it must be limited to accredited investors.

Alternatively, under Regulation S, you can offer shares only to non-US investors. For example, Robinhood could offer tokenized shares in places like the United Arab Emirates or Japan. It’s hard to enforce these geographic restrictions on a digital platform, but it’s possible. Binance and others have done it.

Magazine: Does tokenization or using offshore jurisdictions exempt companies from disclosure requirements?

Chu: Absolutely not. Any company that tries that will land in serious trouble. It’s not a loophole. Regulators worldwide follow common principles under international bodies.

The problem is that people think if it’s on a blockchain or offshore, it’s immune from securities law. It’s not. Tokenization doesn’t excuse you from disclosure or licensing requirements. Even if you’re in a jurisdiction that hasn’t explicitly banned this, the moment you touch retail or promote investment returns, you’re in securities territory.

Magazine: What enforcement challenges arise when tokenized stocks are issued by offshore entities?

Brisov: Regulators can and do enforce securities laws across borders. Take the example of TON. They raised nearly $2 billion globally — only $700 million came from US investors. Still, the SEC froze assets. US, U.K. and EU court orders carry enormous weight internationally.

If you’re offering tokenized shares from, say, the British Virgin Islands or Seychelles, you’re still under threat if you target global investors. Even if you put a disclaimer saying you’re excluding the US, that only works if you actively restrict access. If you simply say it but let anyone invest, US law will still apply.

The SEC has a long reach. If US investors are involved or even just have potential exposure, the SEC claims jurisdiction.

Murat: Reporting obligations also vary significantly. Even when offshore issuers are obliged to file Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) or Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs), those reports are typically submitted to their local financial intelligence units. This deprives US, UK and EU authorities of vital intelligence, unless the transaction can be linked to a known wallet or counterparty through advanced blockchain tracing tools. However, even with such tools, tracing illicit funds is often only effective when matched with off-chain identity data — data that many offshore platforms either do not collect or are unwilling to share.

Compounding these issues is the use of decentralized recordkeeping. Some tokenized equity systems operate on decentralized networks, meaning there is no central entity with the power to freeze suspicious funds or enforce compliance actions. While the blockchain itself may be transparent, if issuers or trading platforms do not maintain reliable KYC records off-chain, or do not integrate with blockchain analytics providers, the trail of ownership and responsibility remains fragmented.

Regulatory authorities are beginning to respond to these issues. In the EU, the Transfer of Funds Regulation (TFR) expands the Travel Rule to cover crypto transactions, while UK and US authorities are increasing pressure on intermediaries — wallet providers, payment processors and platforms — to adopt risk-based compliance measures.

Ultimately, the use of offshore platforms to issue tokenized stocks without adhering to high-standard AML controls presents a significant threat to financial integrity. Unless these platforms adopt meaningful KYC, reporting and information-sharing practices, they will remain vulnerable to abuse and increasingly likely to face enforcement action or restrictions by major regulators.

Yohan Yun

J1mmy.eth once minted 420 Bored Apes… and had NFTs worth $150M: NFT Creator

NFT collector J1mmy.eth trades like Warren Buffett, his collection peaked at $150 million, and he once minted 420 Bored Apes with Pranksy.

Read moreWall Street disaster expert Bill Noble: Crypto spring is inevitable

“It’s 10% up or 10% down each day. I don’t have to wait five years in between crises. As a matter of fact, I only have to wait about 45 minutes.”

Read moreBrandt says Bitcoin yet to bottom, Polymarket sees hope: Trade Secrets