There is nothing romantic about suicide. Yet, ironically, Goethe’s tragic tale The Sorrows of Young Werther, in which the protagonist Werther commits suicide, is widely regarded as the spiritual epitome of the Sturm und Drang — the movement that gave rise to Romanticism.

Now, in case you’re wondering — no, cryptocurrency has nothing to do with Romantic literature. This story is about the strange events that unfurled in the years following Werther, and the effects of the forces behind those events on the blockchain industry today.

Soon after Goethe’s seminal work was published in 1774, something very obscure happened. Young men from Central Europe, living mainly in Germany, Denmark and Italy, became obsessed with the novel and started mimicking the main character. First, youngsters started imitating how Werther dressed: dark boots, yellow trousers, a matching waistcoat and a blue jacket. After that, things escalated. An entire cult grew around the novel; boys started mimicking how Werther spoke and acted toward girls, artists began selling illustrated Werther-themed cups, plates and woodcuts, and someone even designed an “Eau de Werther” perfume in an attempt to cash in on the fever.

This, unfortunately, wasn’t the end of the craze and things soon took a morbid turn. A wave of copycat suicides followed; the victims were mainly young boys wearing the same eerie uniform, committing the act in the same fashion, using the same kind of pistol.

The novel was rapidly banned.

The Werther effect

Two centuries later, in 1974, sociology professor David P. Phillips, who was the first to connect the dots and coin the term the “Werther effect,” published a scientific paper on the influence of suggestion on suicide. The study showed evidence that suicide rates were increasing immediately after a suicide story was publicized in the media, and that the more publicity the story attracted, the more significant the increase in suicides thereafter.

The Werther effect epitomizes the core thesis behind the social contagion theory. Sociocultural phenomena like affect, attitudes, beliefs and behavior spread through populations as if they were infectious. The social contagion theory views cultural traits as analogous to mind viruses or thought contagions, reproduced from one mind to another through mimicry or communication.

Does this ring a bell?

In his 1989 book, The Selfish Gene, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the term “meme,” defining it as “a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation and replication.” The core idea behind memetics is that memes are discrete units of culture that spread by replication and, like genes, differ in their degree of fitness or ability to adapt to the sociocultural environment in which they propagate. In different terms, memetics is grounded in the Jungian idea that people don’t have ideas, but rather that ideas have people.

The meme in the post-Selfish Gene era is reminiscent of the crypto industry at the peak of the initial coin offering craze that ran from late 2017 to early 2018. Just as the myriad crypto influencers and celebrities back then made all sorts of ambitious claims about the potential of blockchains and shilled all kinds of dubious tokens, the “science of memetics” — as it came to be known — made the same type of overhyped claims on behalf of memes and promised to offer a new, unifying theory of culture, one that transcended the traditional anthropocentric conceptions of culture, personal agency and free will.

The overblown claims of pan-memetics, extreme reductionism and lack of empirical support for the core thesis are just a few of the many reasons why meme theory hasn’t caught on in the academic world. Regardless of this, however, the theory is developed enough to be at least partly operationalized by adopting the meme’s eye view — an imperfect but handy tool for anyone investigating culture.

Crypto tribalism through the meme’s eye view

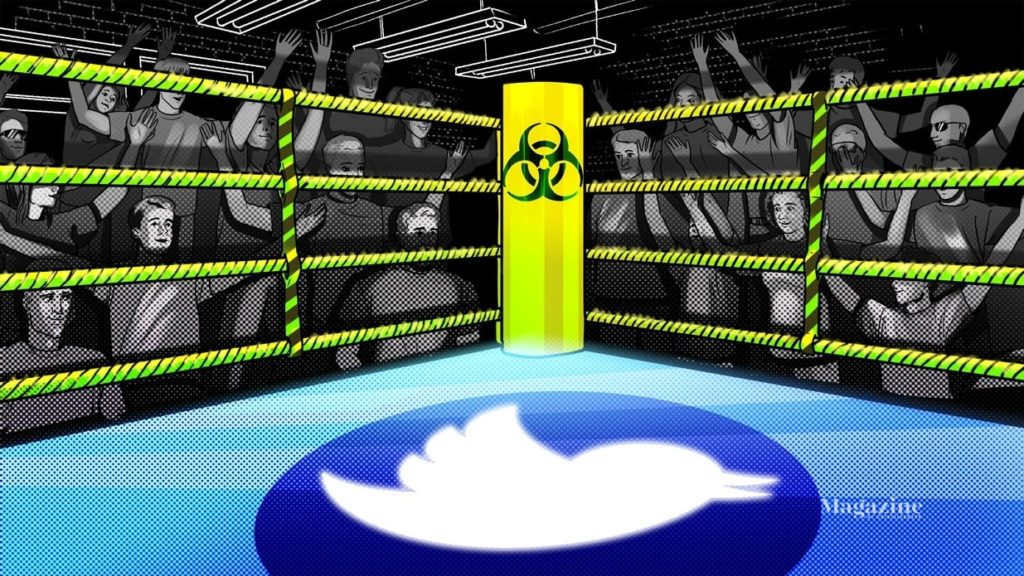

The crypto community is deeply factionalized and, as a result, almost unbearably toxic. Much of what you see on Twitter, Reddit or Telegram is no-holds-barred tribal warfare.

The Ethereum tribe is fighting the EOS, Tron and Tezos tribes; the Bitcoin tribe is fighting the Bitcoin Cash and SV tribes; the XRP army is threatening the life and family of anyone daring to say anything negative about Ripple; maximalists are parroting HODL and calling every other project a “shitcoin” — it’s chaos all over.

What’s more, most beefs are often not even produced by the anonymous masses or the company-sponsored shills and astroturfing bots, but by the talking heads: the journalists, high-profile developers, lawyers and entrepreneurs.

Mike Dudas of The Block and podcast host Peter McCormack have both built their businesses on the back of engagement created by picking endless fights on Twitter. Vlad Zamfir, with his non-meta quasi-trolling “legal thought leadership,” has single-handedly managed to increase the relative risks of stroke and seizure by a statistically significant margin in the small subset of legal professionals in crypto. Changpeng Zhao, CEO of Binance, has threatened journalists with lawsuits, and Justin Sun of Tron has publicly vowed to sponsor cyber-harassment campaigns. To top it all off, there’s Udi Wertheimer, the legendary crypto-developer-turned-Twitter-journalist riling up the entire Ethereum and DeFi community all by himself.

For these exact reasons, many prominent people in crypto have contemplated rage-quitting the industry and going back to their old, pre-crypto lives.

The notion of quitting crypto and “life at the cutting edge of technology” in order to regress to living as a caveman — as a doctor, a professional poker player or a measly helicopter assembly line designer — is as absurd and ridiculous as the idea that tribalism is avoidable and somehow detrimental to the crypto industry.

The currently prevailing narrative regarding tribalism within the community is that we could make so much more progress if we could all just get along. However, the whole point of Hayek’s denationalization of money — perhaps the fundamental idea behind crypto — was to detach cash from the state and, consequently, arrive at better money by having many private and decentralized currencies duke it out on the free market.

Does nobody see the irony?

Not getting along is precisely what got us from an obscure forum post to a $250 billion market cap in just over 10 years. Aside from being an essential part of the human condition, arguing over ideas — even if just trolling or trash-talking the other camp — is a driving force behind all technological progress. War is terrible in many ways, but expedited technological advancement isn’t one of them. Thinking that fighting over ideas is a waste of energy is the same as thinking that proof-of-work is a waste of electricity — it’s factually correct in some sense, but it’s missing the entire point.

During the Cold War, tribalism was, among other things, what got humans to the moon. And things aren’t much different today — tribalism isn’t what’s stopping crypto from going to the moon, it’s the toxygen fueling the rocket. Factionalization allows us to test many different ideas and visions in parallel. It might be toxic to the hosts, but invigorating to the ideas.

The anthropocentric approach sees the culture war primarily as a war between individuals. It needlessly makes things personal and takes a perfectly natural evolutionary process — the clustering of human behavior in time and space — and misinterprets it as primitive and uncivilized.

Adopting the meme stance is a much better heuristic. By observing tribalism through the meme’s eye view, we see the crypto space for what it is — a battleground of ideas. Largely unrefined, but potentially hugely disruptive ideas. In this regard, tribalism is not a bug, but a feature. Not only is it unavoidable, but also healthy for the industry in the long run.

The bullish case for tribalism

While we may like to think of our opinions as our own, social contagion evidence suggests otherwise. Rather than “having” beliefs and ideas, in some very real sense, beliefs and ideas “have” us. Psychologist and memeticist Susan Blackmore has gone as far as to call us meme machines — suggesting we’re nothing but temporary hosts of memes that are fit enough to win the war on our attention and mind space.

Acknowledging the bullish case for tribalism necessitates a radical shift from the host’s point of view to the meme’s point of view. Take, for example, the clash between the two opposing subcultures within the larger Bitcoin tribe — the digital gold camp vs. the digital cash camp. If we analyze the conflict from a conventional standpoint (as everyone currently does), we see a bifurcated community continually exchanging ad hominems, arguing with hasty generalizations and appeals to authority, abusing strawman and red herring arguments while digging ever-deeper trenches over what is, from a practical standpoint, a largely superficial issue.

If we analyze the same phenomenon from the meme’s eye view, however, we see a clash between two distinct, very fit memes — both of which represent two completely legitimate visions for what is, in all reality, a new and never-before-seen financial asset. The two memes are going through the same assimilation, retention and transmission stage of replication, but they vastly differ in expression — the “digital gold” meme influences the hosts to hoard Bitcoin (buy and HODL), while the “digital cash” meme implores hosts to use or spend Bitcoin as currency.

According to memetics, nothing but the fitness of the memes will ultimately determine how the digital asset in question will be used, designed and eventually regulated. Memes, like genes, have no cognition or foresight. They have algorithms that drive the process of natural selection. The successful replication and propagation of the memes is, therefore, independent of our conventional criteria for “good” or “bad” (e.g., truth, science, ethics). In this regard, “good” ideas can become extinct while “bad” ideas can thrive.

Nobody can predict the final outcome of the meme war. Both the digital gold and the digital cash memes may survive, for example, by adapting to maximize replication within two entirely independent niche subcultures (something we may already be seeing with the split between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash). Another scenario is that the less fit of the two slowly withers away and dies, while the other triumphs and becomes the default meme within the Bitcoin tribe.

Whatever the outcome may be, these and all other crypto-native memes must go through the same evolutionary process of mutation, selection and replication, while the community must go through the same repetitive process of fragmentation, dissolution and consolidation. It’s how the blind, purposeless churn of evolution works, and there’s no way around it. The calls to end tribalism are meaningless and boil down to nothing but cheap virtue signaling.

Nothing can stop an idea whose time has come

Even though memetics is far from being a full-blown social theory and may very well end up in history’s dumpster of initially promising but ultimately failed ideas, the crypto community can still use the meme’s eye view to zoom out from the drama and appreciate the fact that antifragile systems — which is supposedly what everyone’s trying to build — are not hurt by, but rather gain from, the exposure to stress and disorder.

The shills, the scams, the Ponzis, the bugs, the hacks, the forks, 51% attacks, the shady influencers and cult leaders — all of these are healthy stressors that help the crypto industry evolve and become even more antifragile in the long run. What’s more, only those wholly immersed in crypto are aware of these stressors. However, as soon as you leave Twitter, poof — it’s all gone.

The sun still rises in the same sky and the external world remains undisrupted — as if Bitcoin was never invented at all.

Outrage as $1.8B ‘DGCX’ crypto scam ringleader mocks victims: Asia Express