In the precariousness of Web3 open-source code, iterative development and “move fast” ethos, things break. And through breaking, things are also made. A new project allows anyone to create a copy of someone else’s NFT, aptly named “Mimics.”

But how does Mimics work, and what does it mean for the NFT art market to have a new variety of fakes? And will it result in token standards being upgraded and improved?

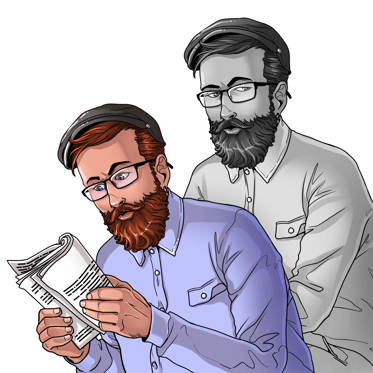

I met the anonymous founder of Mimics in a “Web3” office that was brimming with software developers writing lines of code as they nodded their heads in time to deep house and sipped cups of tea.

On semi-regular occasions, I drop in to visit some local devs in the blockchain space and learn more about what they are working on. They have always been welcoming and jovial, inviting me to share in their ritualistic Friday afternoon “meme creation hour” and have a go at spinning the in-office DJ decks.

They even offered me a desk to work from there for free, provided I clean the office once a week. I told them where to go (they were joking, but perhaps only half-joking as I stared at the overgrown vines living in the exposed beams in the roof).

It was at this office that I met the anon who would later take an extended sabbatical from their hand in engineering successful projects and, in their tinkering, discover and open-source a way to mimic your NFTs.

Stealing your NFTs

“I think I just broke the NFT market,” the anonymous founder told me flatly.

“Really? How?” I responded.

It turns out that art NFTs have a line of code in them called “tokenURI” or “URI” that acts like a pointer to the image being displayed. As the code is public, you can redirect your own NFT to make it look like anyone else’s. If you want your NFT to display a Cypherpunk, a Bored Ape, or how about a Pudgy Penguin? You got it.

This means that your rare and expensive cartoon image NFT can essentially be cloned, not just by right-clicking copy-save as, and making another NFT of the same image but as a verifiable copy that has remnants of the real thing through code. Users rushing to clone a Bored Ape should beware, however:

“This could be a blatant breach of copyright or other IP,” states Australian crypto lawyer Joni Pirovich. “To determine rights that attach to the ownership of the token, and any image or metadata associated with the token, the buyer should try to identify whether any terms and conditions and any IP license applies to the ‘sale.’”

Many projects launch or resell on NFT marketplaces such as OpenSea without drafting their own terms or licenses and without revealing their identity. In these cases, they are not acting to protect any IP they own or allowing a person to understand who the copyright author may be and whether there is a human or computer that is generating the art and/or data. In Australia, copyright comes into existence when it is created by its author. In other countries, such as the United States, copyright is a registration system. NFTs (and associated metadata) are available globally and often without clear terms. This makes it unclear what IP laws apply.

Noticing that few others have cottoned on to the ramifications of how the NFT metadata works, the creator(s) of Mimics have open-sourced how to do it, of course.

Into the code

When it comes down to it, NFTs are really just tokens with a bundle of metadata. This data about data carries with it all the necessary information for someone else to locate and use it.

NFTs that can be mimicked via their metadata (so far) are ones that adhere to the most common ERC-721 and ERC-1155 standards.

ERC-721 and ERC-1155 standards provide two core sets of functionalities: controlling ownership of the token and getting data from the token. The latter function usually returns the appearance of an NFT to a website or wallet in order to display the NFT when “called” by a smart contract.

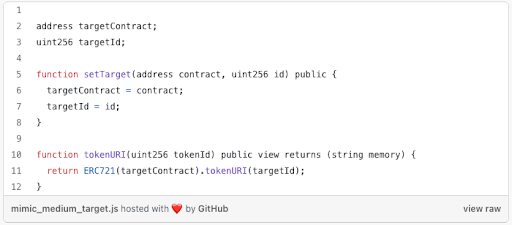

The trick with Mimics was realizing that the tokenURI can be called by a contract address. Particularly, it can be called inside the tokenURI function of another contract. Mimics hacks the metadata, allowing you to make an NFT that mimics the digital media attributes of another, such as an image or animation. Anyone anywhere can run this URI metadata function. Instead of the function being permissioned in the ERC standards so only the user can view an NFT or grant permissions to other sites to view it, it is public.

I ventured deeper into the Discord channel…

The Mimics project has open-sourced a codebase so you can mimic the “targetContract” and “targetId” of another NFT and make your NFT look just like that NFT.

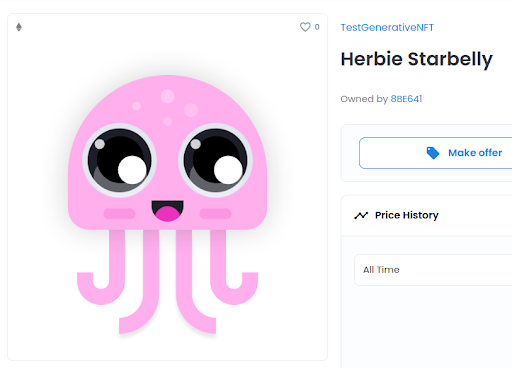

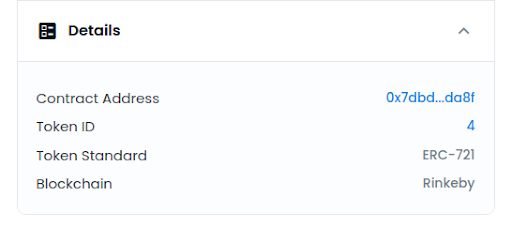

“How about this cute jellyfish?” states the Mimicologists Guide docos.

On OpenSea, we can copy them from the page URL, the “Token Id” is the number on the far right, and the “Contract Address” is just to the left of it.

The Mimics contracts are now available. In true Web3 style, Mimics are permissionlessly available but technically a little tricky to access.

Initially, there was no web page front end, so you had to go on an “expedition” to interact directly with the “guild contract” on Etherscan. This was recently updated.

In a year that has seen some major heat in NFTs, how could Mimics affect markets? In the current context of market crashes, these lines of code and the token standards they draw upon have some serious implications for NFT owners, developers and the market at large.

What does this mean?

At this stage, Mimics don’t have implications for NFTs beyond artworks (such as copying NFTs with distinct functionalities to attest to membership). Only the metadata such as name, description, media and other attributes that are provided by the tokenURI can be mimicked. For something to be proxyable, it needs to be an attribute that an NFT provides on a public function or interface (meaning it is accessible by all users and other contracts on Ethereum) and not validated in any way by the website, service or contract receiving it.

Instead of being “law” to provably enforce the rules of the system, code here is the undermining factor in NFT security. Mimics prove the thesis by well-known cryptographer “Moxie” that crypto lacks cryptography in some respects — referring to cryptographically secure components of the codebase that make aspects of unique ownership provable, private and/or permissioned. Ironically, someone has already used the mimic contract to copy Moxie’s NFTs.

In some way, Mimics demonstrates a coordination failure in how open-source standards are made, peer-reviewed and adopted in Web3. This is until you see that Mimics actually forms part of the narrative of how these standards may evolve over time.

Setting a standard:

So, was this all a scam? A Ponzi scheme to short the market or flood it with fakes?

No. It is a game. Mimics are another example of the playful aesthetics and hacker ethic of “Web3” culture. It is a light-hearted hack with some serious implications.

Just as in the traditional art market, NFTs can be faked through Mimics. And just like in traditional art markets, this fact challenges users to take responsibility for tracing the provenance of what they’re buying. Identifying vulnerabilities is how infrastructure is strengthened.

“I think it’s cool having copies, as the originals can always be easily verified,” states BokkyPooBah, serial NFT artist and open-source software advocate. “Perhaps it means people need to be educated on how to verify authenticity, and marketplaces and tools should make it easier to verify.”

Bokky’s NFT collection features originals and offshoots of well-known collections, including MoonCats, a “Kevin’s collection” Bored Ape and a “fast food” CryptoPunk.

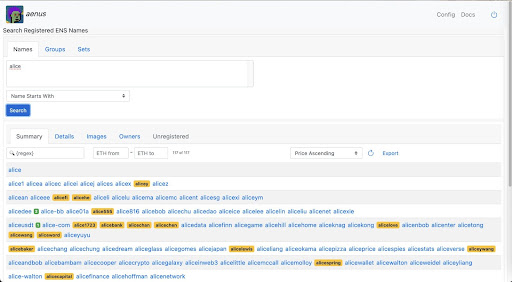

The purpose of a blockchain ledger is to prove provenance, yet it is still extremely difficult to verify that an NFT is from a legitimate artist. For example, on the Ethereum Name Service (ENS), people make close copies of well-known artists’ domain names by replacing “1s” with the letter “l” to trick buyers into thinking it’s an original. For this reason, Bokky is working on a tool to research ENS names, in the hopes of helping the community at large to spot real versus fake NFT collections.

Mimics also enable new possibilities for what people will build next in the world of NFT art. Perhaps the first mimics will accrue their own value as “authentic” fakes.

The current Mimic contracts only allow one copy of an existing NFT to be made. This could add more value to originals if people want to create provable copies of famous NFTs. For example, some argue that the many clone projects of CryptoPunks actually add more value to the OG version.

The Mimics codebase also includes a defense mechanism. By setting up a “Shield of Essence” and activating the “aura,” the shield will protect all NFTs on the same account from being copied (known as “poked”) by mimics.

Of course, the code is open-source, meaning that shields will only block Mimics but not other iterations of proxy NFTs. Now that the secret is out, it is possible to copy the Mimic contracts themselves, make a few changes, and mimic everything over and over.

Mimics are a call to action to improve NFT standards and decentralized infrastructure at large. The hacker-developer behind Mimics does not just want to break things, but to build.

“Current NFT standards do the opposite of protecting your art at the code level,” states the Mimics project blog post. While wondering if they’re breaking the NFT market, the hacker also provokes, “Maybe this article and the associated code will provide some impetus” for a future where ERC standards are improved and iterated on and become even more widely adopted. The goal is to build a better standard for their information infrastructures.

Improving token standards requires stronger permissioning at the code level — meaning creators of NFTs expressing their preferences at the code level. They would get to decide where that NFT is displayed rather than it being pulled publicly. Technically, you can create an NFT that blocks this at the code level and still be ERC-721 or -1155 compliant. Yet people aren’t paying enough attention at the code level of the NFT market to put measures inside the function to detect contracts that try to run the code and block them.

Mimics is one example of the broader ethos of Web3. The project embodies core themes of the Web3 ideal: participatory building, self-organizing, and owning one’s own infrastructure (or at least, expressing preference over how it is owned and governed).

Web3 originates from hacker communities. Hacking is about reordering. “The politics of technology are about ways of building order in our world,” states infrastructure scholar Langdon Winner. The ways that the dynamics of reimagining, deleting and revisioning will unfold can never be fully anticipated in advance.

Commonly, in places where Web3 fails, it rises from its own ashes like a phoenix. Epic failures such as Mt. Gox and “The DAO” hack have helped lead to the proliferation of governance composability and practice today. Understanding this helps to place the recent Terra’s LUNA and TerraUSD market crash in context.

NFTs may be the same with projects like Mimics, which chip away at the legitimacy of what currently exists, in order to build something better.

Kelsie Nabben

Binance, Coinbase head to court, and the SEC labels 67 crypto-securities: Hodler’s Digest, June 4-10

The SEC sues Binance and Coinbase, and labels dozens of coins as securities. Both the crypto exchanges paused services while promising legal battles in courts.

Read moreCrypto’s ‘pro-rioter’ glitch artist stirs controversy — Patrick Amadon, NFT Creator

NFT artist Patrick Amadon is proudly “pro-rioter,” as Hong Kong Art Week discovered, and he’s at home in crypto, where everyone’s a rebel.

Read moreBitcoin ‘bull pennant’ eyes $165K, Pomp scoops up $386M BTC: Hodler’s Digest, June 22 – 28